from pastelegram.org, June 2011 – April 2014

An interview with Kristina Felix, regarding Artificial Emotional Spectrometer and its conception

I called up Kristina Felix at her home in Chicago and after hello-ing back and forth I began the interview, saying, “Let’s start off with taking about Artificial Emotional Spectrometer. The obvious first question is: how did you conceive the project, and why does it look the way it does?”

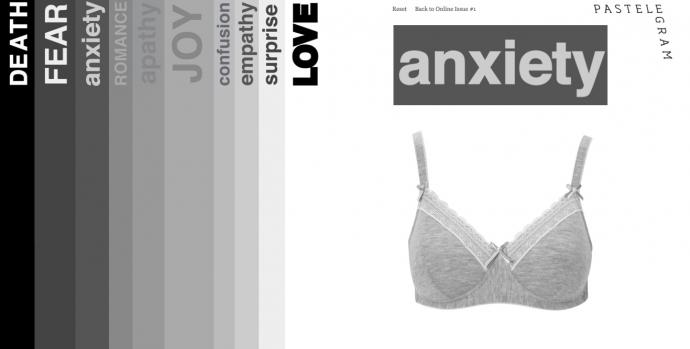

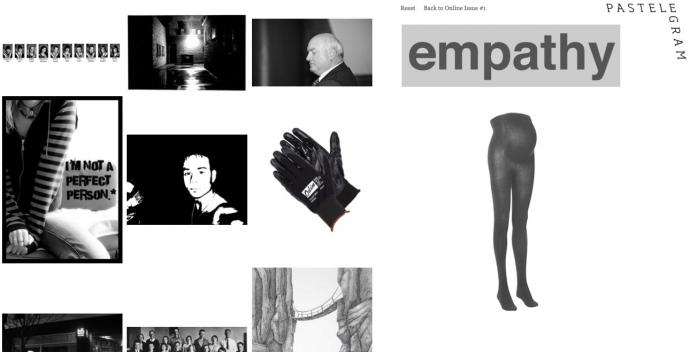

Kristina Felix, Artificial Emotional Spectrometer (screenshot), 2012.

“I was thinking about what a project that uses the Internet would look like,” began Felix, “I wanted to conceive of a project that uses the Internet as a medium or pokes around the Internet in a way that doesn’t feel as manipulated as it usually does. I feel like every time I get on to Google or open my laptop to look at the news, whatever I find is predetermined since Google’s algorithm pulls up certain results before others. And I wanted to devise a system where chance could happen. I wanted to use Google to draw meaning from its results that wouldn’t otherwise be there.” Felix paused, “I guess the first question I was asking when I was starting is: how much of us—us being the people that use Google and other search engines—how much of us is in that algorithm? I see it as this big pool that we all contribute to, and the results are based on what that pool is being fed—“

“But Google determines which results float to the top.”

“That’s what I’m talking about with predetermination. There’s no nuance in Google—that’s why it’s so successful obviously—but I’m asking questions about what isn’t visible or what isn’t being sent into the pool.”

“So with your pairing of words and images,” I began, “were you thinking about the fact that online we see words and images, that are often together in some way? Like the image is always somehow affected by the words around it.”

“Going back to where the project came from,” began Felix, “Initially it was about language, how Google uses our language to give us images, or how that works. Maybe it’s a silly question, but I think it relates to bigger and broader things. But I turned the words into images, in a way,” said Felix, referring to the word-blocks, which register to the computer as an image. “I made the letters in the word more orthogonal so that what you get would be more visually interesting. Part of it was making words into images, using a series of shapes.”

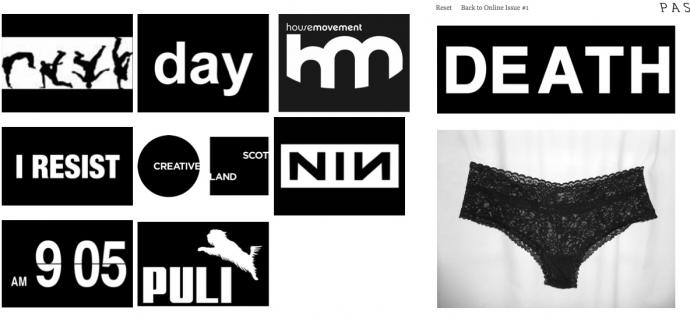

“And you click on that word-image and Google finds images that are visually similar to the word made into an image.” I was thinking, for example, of clicking on Felix’s “DEATH” word-image, which resulted in a lot of black boxes containing flat white graphics.

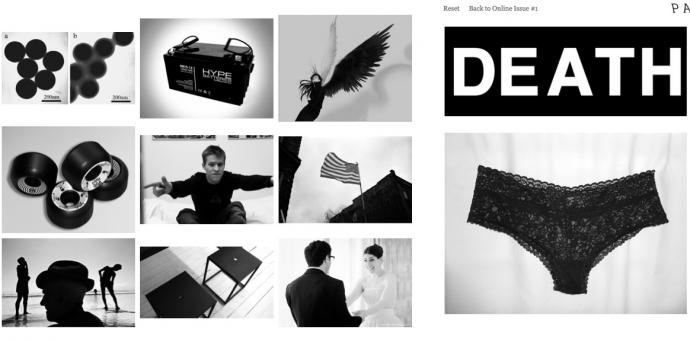

Kristina Felix, Artificial Emotional Spectrometer (screenshots), 2012.

“It’s kind of a ridiculous premise, that you would look for images close to this word image. And that was part of it, that humor; which also comes in the images of the underwear, like the ridiculous Abercrombie and Fitch boxers. It’s also joking about and pointing to the origins of the Internet.”

“It’s funny to me,” I interjected, “the way in which the meaning of the underwear ends up connected to the meaning of the word. I’m like, what is it about the panties paired with the word ‘DEATH’ that is more death-like than the boxer-briefs that accompany ‘surprise.’ And I’m like is there a surprise in those boxers, and do I want to know what it is?”

“I like that that happens,” laughed Felix, “but I wasn’t really thinking about that. I feel like the Internet is what it is because of porn."

“Is that what you were getting at with the ‘origins of the internet thing?’”

“Yeah. I don’t really know but I feel like in the beginning there were chat rooms, child predators—and I guess they’re still out there—but what seems to have propelled the Internet into this huge fucking animal is sex, porn, people trying to find dates online, and people trying to show their life on Facebook.”

“All of these things, but fueled by sex and or love or both,” I paused. “So you’ve got two things, as I see it. Well, more than two things but let’s go with two for now. You’ve got an interest in language and how language works, and the interest in how sex and love works. It seems to me that a lot of that connects to Lojban, that invented language you were thinking of working with for the project in the early stages. So I was thinking that we should maybe talk a bit about that as well.”

“Totally, but in how it relates to the project or my thoughts on it in general?” Felix asked.

“Either one, whatever.”

“Well, I’ve always had this interest in invented language. I hate to sound sentimental about it, but it might have something to do with being from a bilingual home, and having summers where I would only speak Spanish and read everything in Spanish, and coming back to school and speaking English. Now that I’ve gotten older, I think it impacted me in some way. Lojban—well that idea of invented languages came out of that interest in wondering what … “ Kristina paused to collect her thoughts. “So there’s this theory right, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. It basically posits that the language you speak shapes the way you see the world. In certain languages, say, if blue is not in their vocabulary then they can’t see blue. And with the idea of an invented language, it’s the reverse. Instead of language making culture, people in that culture make language. I love that most invented languages are all for the sake of communication that is clear. It’s utopian, since the ideology concerns universal language as the solution to wars, misunderstanding and relationships.”

“Do you think that most of these invented languages are invented because this Tower of Babel problem, that many of the misunderstandings that cultures and individuals have result language, so that if we fix the language we fix the cultural or social problem?”

“Yeah, that’s what I’m wondering. If language shapes our mind, then if we all spoke the same language or had it as a second language, would that somehow contribute to Eden, or … of course, that’s impossible to know.”

“But specifically you were talking about Lojban, instead of, say, Esperanto. So why Lojban?” I asked.

“I’m not an authority on either language. I enjoy reading about both, but to me the biggest difference is that Esperanto looks different,” Felix noted. “Esperanto is just letters while Lojban has a lot of accent marks—it’s a really interesting language to look at. And the other thing about Lojban that I find fascinating is that it’s based on logic. It’s an attempt to remove any kind of emotion from expression. Which sounds horrible, since how is that idyllic? But it has something to do with intonation and the subtle underlying meaning of things as what causes misunderstandings and confusions. And if we’re all speaking a language that’s based on logic and everyone has to say things in the same ways, then there’s no way that it could be misinterpreted. So the biggest difference is that Esperanto is a little hipper, and Lojban is nerdier,” she finished, laughing.

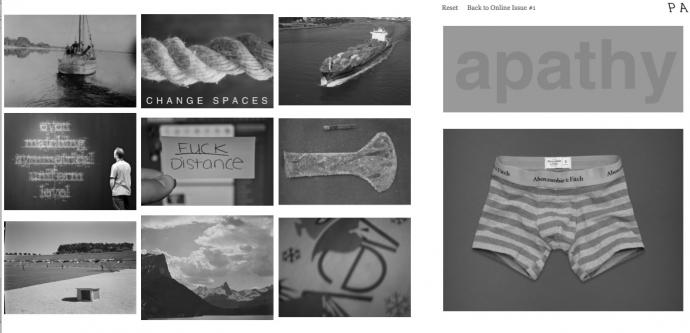

Kristina Felix, Artificial Emotional Spectrometer (screenshot), 2012.

I decided to bring the conversation back to Artificial Emotional Spectrometer. “So, people start out with words, a selection of words that are tied to a selection of grays. The word’s meaning is already affected by the color that it’s paired with, which I suppose you could draw meaning out of, like the fact that ‘DEATH’ is on a black background and ‘apathy’ is on grey text on a gray background.” I paused. “What happens is that the words go through a series of operations, right? You click on one and it becomes paired with an image, and then you click on either the image of underwear or the word image, and then what appears next to that pairing is whatever it is that Google comes up with as ‘visually similar.’ What is it that you think happens to the meaning of that word through that series of operations?”

“Well, I think it points back to the medium of the Internet. Thinking about Google’s algorithm, it probably works by counting the number of pixels in a certain color or averaging them or taking a shape. I’m sure the algorithm is really complicated, but it’s basically taking visual averages of this image of a word (or image of underwear). What ends up happening is that you get all these pictures that kind of look like the image of the word. And hopefully what happens is that you start to look at the word exactly like you look at the images. You might not necessarily try to read the images like you would read the word, but maybe having them next to each other confuses the line between reading something, like language, and looking at something like an object, or an image. So hopefully what happens is that the image is confused, or the word or vice versa.”

“It’s also interesting, how the results sometimes make sense. You’re like ‘Okay, I can kind of see how those are visually similar.’ In other cases it’s not so easy to draw the connection,” I noted. “Perhaps it gets back to the Lojban issue, where you have an operation happen that is supposedly logical but ends up not being so. The machine that is making the decisions which result in the images … well, because there are so many possibilities, it’s almost completely irrational what you get back sometimes.”

“Yeah, and I love that automation. I think that’s one of the reasons it works is because there is no emotional decision making, other than the first decisions. Obviously I chose the images and the colors of the words. Those images are made and they’re kind of just thrown out there. Sometimes, depending on the day, the results change daily, I noticed.”

“Actually, if you click on an image again the results will change right away.”

“Yeah. And is that us changing the cloud that these images exist on, or is it they’re just climbing in the ranks? The algorithm is not changing, so what is?”

Kristina Felix, Artificial Emotional Spectrometer (screenshot), 2012.

“But okay … but there is emotion, so to speak, in the spectrometer. You picked words that represent emotions. Why?” I asked.

“Having words for emotions is like having images for words. Those things don’t really translate. When I say the word “love” and someone hears that, their mind understands through a series of experiences where they felt that emotion. I like the idea that it’s drawing on some sort of personal relationship with this word. I guess that could be any word. I could say “apple” and you would have had this weird experience with an apple—“

“I love apples,” I joked.

“I do too.”

This article is part of “Width and Against” by Kristina Felix. Other parts of this project include:

Artificial Emotional Spectrometer by Kristina Felix

100 Titles for a Project by Kristina Felix and S.E. Smith

Bodies of water: a lyric circle by Anne Marie Rooney

And our editor’s statement