from pastelegram.org, June 2011 – April 2014

An Interview with Travis Kent, on the Occasion of his Exhibition at Domy Books and the Publication of his Zine, Both Titled All Best.

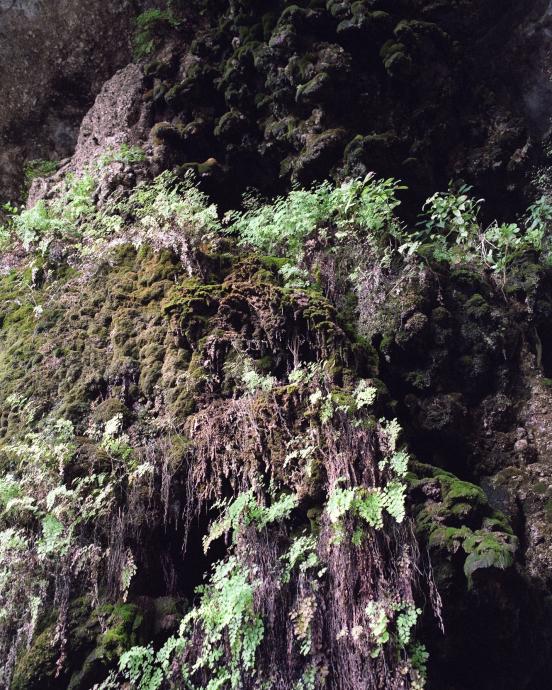

“Let me ask you about this photograph,” I said, pointing to an image of Carlsbad Cavern in New Mexico.

Travis Kent, Carlsbad Caverns, NM.

“It’s weird because Carlsbad is such a tourist thing,” Travis Kent began explaining. “The whole experience is pretty removed from anything resembling what it was when people first discovered it. It’s all very theatrically lit on the inside.”

“What were you doing in New Mexico? Why did you go?” I asked.

“I think it was more a point between this point and this point,” Kent replied. “We had some time. We actually drove out there for a wedding and we decided to take a couple extra days and stop at the Grand Canyon. We slept at the Grand Canyon, which was great, and the next day when we woke up we were supposed to drive to this wedding that was happening that day. But at this point my friend decided she actually didn’t want to go to the wedding, so we didn’t. We decided to just drive back and take the long way, we stopped off at Carlsbad on the way.”

I laughed.

“There’s two entrances if you want to get to the thing. There’s an elevator which goes straight down, and there’s also a more original entrance…“ Kent went on, referring to the cavern entrance in the photograph.

“Oh, where the explorers found it?”

“ …which is now paved so it’s pretty funny. So you go on a 1.1 mile hike or something and you walk down. And it just keeps going down into the cave, some 700 feet. So I took one picture walking in. The next picture was the reverse, where I’m down looking up.”

I asked Kent why he picked the looking-down photograph instead of the looking-up one.

“I could get very literal about this or not,” he replied. “It’s hard to say because the nature of the show is pretty heavy to me and I’m looking down at a lot of it. Aside from that, it’s just a stronger image. The other image was not as successful. Maybe I could’ve taken more than one looking up, and another one would have been more successful. But the one that I shot was not as good as this one. It makes it easier to edit, if you just shoot the one. I think the other images I shot down there were a stairwell, one of some rangers. And then another one of the needles coming down at you.”

“You mean, stalag –“ I tripped over the word. “Stalagmites or stalactites. Stalagmites are going up, stalactites are going down. I might have that reversed. I always get it messed up.” I paused and continued, “The reason I wanted to ask about this one is that it seems to me from going to the show and then looking through the zine, you always identify the place where you took the photograph—was this your choice?” I wanted to find out if an idea of place was important to Kent and if so, why.

“Titling was a choice I came to after talking with a couple people close to me. In the past I titled things in a more matter-of-fact way—Stairway, Husky—whatever it might be, whatever the focal object is. For the book I thought it would be more fun for the reader to get this little piece of information that wasn’t obvious to them. Because in titling something as exactly what it is, since I’m putting most of my subject right in the foreground—right dead center, rather—you’re already getting that.”

“You already know the name of the object so why identify them in the title.“

“I previously titled things by imagining someone standing in a room looking at this photograph on a wall. They might motion to their friend across the room, ‘Hey, buddy, did you see this picture?’ And their friend is like, ‘What is it?’ or ‘Which one?’ ‘Oh it’s the one of _________.’ Whatever the word that somebody would say to describe the picture, that’s what I would title them. But because a lot of the images are so matter-of-fact anyway I thought it would be nice to include this little piece of information on top of that.”

Travis Kent, Hamilton Pool, Dripping Springs, TX (left and right).

I looked at the book in front me. I’d noticed two diptych arrangements before the interview: the first with two photographs of Hamilton Pool in Dripping Springs, Texas. The second paired arrangement—also facing each other—featured white cats, one on top of a covered car and the other on some sort of veranda. I mentioned them and Kent asked me to explain why I’d asked.

“I’m trying to figure out how to phrase it,” I began, “because I didn’t start at the beginning and then go through to the end. I started here—“ I let the book fall open to the middle.

“With a zine like this it just falls open to the middle spread. It’s just part of the nature of the thing,” Kent said. “For the moss: though I typically shoot just one, this is an instance where I shot two images of something. I stood here then I stood here, and you see these in their order. I shot the left moment first, and then this was the second,” Kent explained, pointing to the right-hand image. “For the image of the covered car and the cats: I just shoot and build up an archive that I go back to for shows, features, publications, whatever. I try not to look back on what I’m doing too often because then I’ll overthink it instead of moving on. When you do look back you see all these typologies beginning to form, these moments that you’re attracted to. Unfortunately I shoot a lot of cats. And I don’t like to show them and the fact that I showed two… they’re both nice though.”

Travis Kent, left: Bagley Avenue, Los Angeles, CA; right: Landon Lane, Austin, TX.

“I had thought to myself, going through the zine earlier, that these must be the same place and the same cat. And then I looked in the back… It’s funny that there’s this similarity”—I was referring to the point that the zine paired both sets of photographs—“since they come out of these two very different modes of working.”

“Yeah, totally.”

Installation view of Travis Kent: All Best at Domy Books, Austin, 2011; photo: Carling Hale.

“Do you want to know how I hung the show?”

“Yeah, let me know.”

Kent explained. “For this show I chose between thirty and forty images. What I did is I went through and decided each image’s size. Typically if an image is pretty loaded I’ll make it small. It doesn’t need to be so big and in your face. I think the quieter moments—those you can look at for longer—are the ones that should be bigger. With hanging, I went in with these sizes already decided and I hung the big ones first as if there would be nothing else up. Then I went down to the smaller images or the medium sized ones and peppered them in as if that was all that would be in the show. And then the last ones I hung were just to balance out space, just the real tiny ones. It felt fluid, like painting.”

“So the exhibition itself was kind of like a painting. You’re popping in the big strokes first, as it were, then adding detail.”

He went on, “That photograph of my grandfather, at the wake. I would feel weird if I blew it up really huge. I think it works better as a small image.”

“I tend not to like big portraits of people,” I agreed. “It almost looks commercial.”

“This is the first show that I’ve shown portraits at all. I don’t typically shoot people. Which starts to get into my whole process in terms of taking a picture; it goes against a lot of what I typically do. Generally when I shoot, I take one picture of anything, because it’s easy to take a bunch of pictures of one thing. Most of your decision comes in editing and placement after the fact.” He offered an example: “If I have to sit down and say, ‘Well in this one their hand is like this,’ and then ask, ‘What is the meaning, what is the difference between the two images?’ I find myself going nuts trying to decide which of the three is the one to show. So I make things easier on myself. I just shoot one and if I get it, I get it. And if I don’t it’s fine, it wasn’t meant to be. Which works great for inanimate objects and landscapes and such, but for people it’s a lot harder because people blink. Also I’m still kind of a timid person when it comes to that, and I’m still not at the point where I’m photographing strangers, per se.”

“I would imagine that would feel weird.”

“I have to feel pretty comfortable to take somebody’s picture,” Kent noted. “There’s the one photograph of the girl sitting on the bed. And that was such a heavy moment when I was in it, I didn’t know how to deal with it besides hiding behind a camera ..."

Travis Kent, 13th Street, Austin, TX.

" .. Which is kind of sad in a way. But it’s a sad image and it’s not hiding behind that at all. The show, very basically, could be summed up as moments of poignancy for me. I don’t know if I’m laughing or crying but I’m feeling a lot at this particular moment.”

“So you said this is one of the first places where you’ve explored portraiture.”

“Presented it,” Kent corrected me.

“That’s better phrasing. I remembered that photograph of Ben Ruggiero, of course, since I know Ben and it’s hard to forget that beard.”

Travis Kent, Ben.

Kent explained: “That’s the only one that I have a harder time tying in. I was joking at the opening that there was a high plants-per-square-inch ratio in the photographs on the wall. And there’s a lot of foliage in that portrait of Ben, and there’s a little undercurrent of human experience about nature throughout the show.” Kent paused. “No offense to Ben, but I feel like he looks kind of awful in this picture.”

I laughed.

“I’ve got a lot of people who won’t let me take their picture anymore. I always seem to catch these moments of them looking terrible.“

“Well, we don’t look at people ever still. It’s unnatural. The idea that we look at photographs as portraits of somebody is a little strange, because it never actually looks like the person,” I said.

“You know, it’s like, ‘That’s not you, it’s a photograph of somebody that maybe was you a couple weeks ago.’ In a way, that picture of them is still life.”

Travis Kent, Large Rock Duncans Cove, CA.

“One more thing that I want to touch on.”

“Go on.”

“In preparation for this show I was reading and listening to a lot of Ted Berrigan’s sonnets. I don’t know if you’re familiar with them?”

“I’m not.”

Kent explained, “I don’t know too much about poetry, but to break down how he might write one particular poem: it’s like auto-line. He uses this kind of algorithm where he pulls lines from other poems where they maybe didn’t work, or takes a poem and writes it and goes ffswhhhhtttt”—Kent quickly alternated his hands forward and back in a slicing motion—“with the line. So some of them you could maybe put back together, but mostly they just read as these one-off lines that flow nicely because of the way his auto-line works. There’s such an awesome rhythm. I can play some of it for you because I have these recordings of him from 1981. He’s kind of on drugs—he tries to get as many words out as possible before he loses his breath.

“What’s also interesting,” continued Kent, “is that there are like a hundred of them and he wrote them really fast. So there’s a real serial-ness to them. You can be working on something and be peripherally listening to it, and thirty minutes will go by and he’ll say the same line that he said earlier. All of a sudden, though you weren’t paying attention you’ll be like, ‘Oh! I remember that line from earlier.’ Which I like for when I hang a show, specifically because I like playing with the images spread out. I also might put in the same image more than once, to play with the idea that if you’re walking through a space, if you didn’t catch it here you might catch it there. Or maybe it’s a weird déjà-vu moment. Berrigan does that and I love it.”