from pastelegram.org, June 2011 – April 2014

An Interview with Barry Stone, Excerpted from Pastelegram No. 1: The sun had not risen yet / Now the sun had sunk

“We could talk about the process of doing it or talk about the circularity issue. But perhaps that would be being too transparent; I don’t know,” I began.

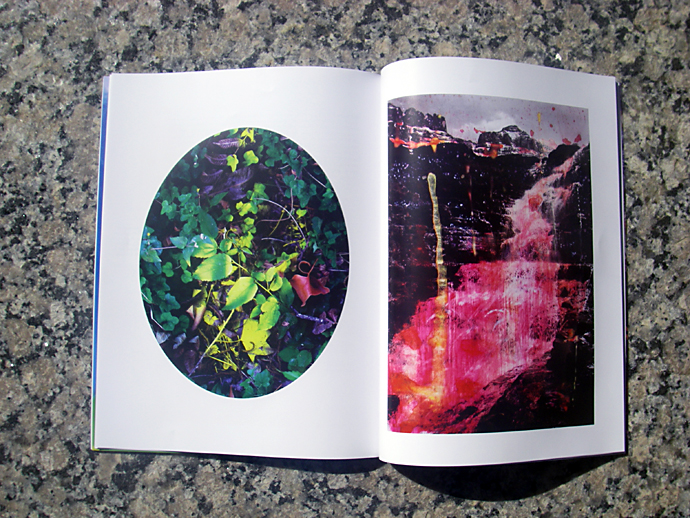

“It’s hard to know how much to reveal and how much to conceal.” Barry laughed; we had discussed this several times before. “How do the images go together?” Barry continued. “Well, I was thinking of the idea of circularity, that we repeat ourselves over and over again through history, not only art history but also social history. And I put the images together so that there’s a mirroring of image types. The first and the last picture echo one another and they build inward as the sequences go. So I think in that sense, there’s a kind of loop in the pictures, although it’s read left to right or in a linear fashion, but I hope that it becomes apparent to maybe the careful reader.”

“You could conceivably go backward to forward,” I said.

Barry answered, “You could, ’cause it’s a loop. Absolooply. But it starts off with that still life of flowers and ends with the tape flower. Both are more or less the same floral image, but one manifests as a collage and the other manifests as a still life. There’s a kind of interruption in the images.”

“Okay,” I paused. “I guess two questions come to mind, but they’re very different. The first is: When did you start thinking about circularity; how did this all begin?”

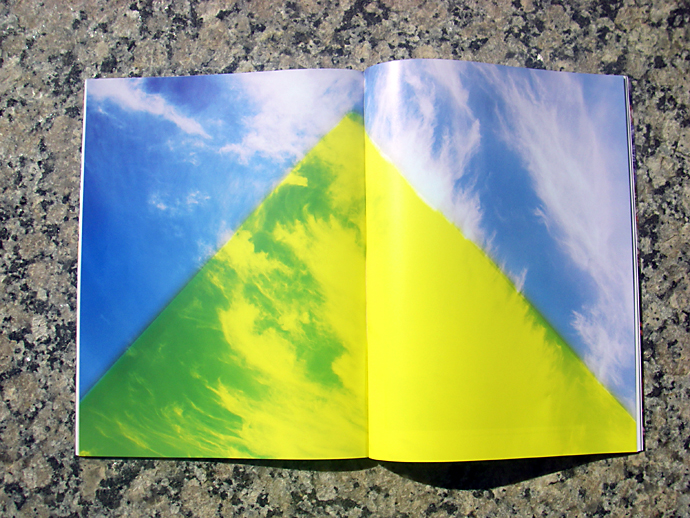

Barry answered, “I think a lot of it tumbles out of a long grappling with ideas of photography and what makes an image interesting. Or if there’s anything intrinsic to the process of photography, be that its indexicality or its fidelity. What that dovetailed into was thinking about photography’s relationship to painting. For example, how we create photographic images along the 2 x 3 ratio, which comes from an average drawn from Renaissance painting.”

“It’s the golden rectangle,” I noted.

“The golden rectangle, the golden ratio,” Barry agreed, “That and all these other ideas are recapitulated over and over again. Not just in art or art historical processes but in a social sense, too.” Barry stopped to think before continuing: “I’ve been thinking a lot about what we value as a society in the face of so many budget cuts—specifically education—the things that I value aren’t being valued. So I think about alternatives to a market economy, maybe a gift economy. … I think about other visions: utopias, Marxist visions of how the world can work or other modes of exchange. I think about how many times we’ve re-envisioned the world and how many times that circles around and succeeds or fails, over and over again. So that’s kind of how the magazine’s theme coalesced. There’s the visual thinking, then there is—and I’m not sure how related it comes out in the pictures—there is a kind of social or political dimension to it as well.”

“Well, I guess the one place where that kind of social dimension would come out is in the excerpt from Sir Thomas More’s Utopia, and perhaps even in Maria Bustillos’ article on David Foster Wallace,” I responded. “It seems to me that Wallace was looking for a utopia that didn’t occur. For Wallace, perhaps utopia was just plain old ‘normalcy,’ but for whatever reason he felt that that was unattainable for him. Accordingly he committed suicide, and then Bustillos goes through his archive at the Harry Ransom Center in an attempt to grapple with that herself.”

* * *

At this point, Barry and I talked of this and that before finally returning to the topic at hand. I returned to the question of photography’s relationship to painting, beginning, “Well I was thinking of examples to these issues that you’ve delineated. One being how to think about photography as a medium but also as a specific history, a history that makes certain requirements of its practitioners ... and many of those requirements have to do with painting.”

Barry answered, “One of the main things that ties it together is this idea of fantasy and fidelity, and photography has a foot in both camps.”

“Right.”

Barry continued: “And the idea that photography offers these highly detailed descriptions of the world which are taken for truth in some sense, at least in terms of an observed happenstance. But they’re also contingent on all kinds of other subjectivities, which makes them fantasy.”

“And we’ve cycled between holding photography up to either of those two poles,” I suggested. “Despite the enthusiasm over photography’s documentary capabilities in its early years—and its uses for police mug shots and journalism—there were still plenty of people doing photomontage and painting on photographs, even in the nineteenth century.”

“That’s why I think the Coburn was interesting in the magazine,” Barry mentioned. “It references that circularity, in terms of showing ideas privileged in a zeitgeist. As Bernard Yenelouis showed, the American trajectory of photography was a strictly materialist or modernist methodology that Szarkowski definitely championed and molded.”

“He glommed on to Stieglitz’s aestheticism and formalism … ” I drifted off.

“Well definitely,” Barry responded. “Seeing things as a camera would see them, a documentary style meant seeing them democratically. That’s definitely what was privileged in America, but at the same time there’s these Pictorialists like Coburn who love soft-focus and amorphous shapes. There’s this moment that I love where some of these hardcore Pictorialism adherents do an about-face and say ‘Wait a minute—to capture the grandeur of nature it’s not about a kind of petroleum-jelly haze on the lens, it’s about acuity and it’s gotta be f/64!’ Suddenly that becomes the modus operandi. Then whole groups of folks call themselves ‘f/64’ to champion this new clarity and this objective vision. All the while in Europe, there’s Moholy-Nagy and Hans Bellmer, and all these other characters that have this kind of parallel history, which now I think has become more the prevalent model, even in America, and has become more the prevalent interest in digital photography.”

Barry paused. “It comes off as the challenging of established dogmas,” he suggested. “For example, just the other day, my wife was saying that they’ve come out against sit-ups all of the sudden.”

“What?!” I was surprised.

“All of the sudden,” Barry explained, “there’s no measurable difference between the ab strength of a dedicated sit-up person and somebody who doesn’t do any sit-ups at all. So all these sit-ups have been done for naught, because we’ve assumed for many years that sit-ups are beneficial.”

“Because they hurt!”

“They hurt, exactly, you’re sore afterward and I guess you could become ripped afterwards. But there’s always this kind of challenge to these established orthodoxies, just because one has to write a PhD I guess, or what have you.” Barry continued, “I see it also in ideas of child-rearing. At first you weren’t supposed to give the kid peanuts until he was seven years old, and now it’s actually imperative that you give the kids peanuts in their first six months.”

“Well, it gets back to utopianism,” I responded. “Because of capitalism we are glutted with things; people have to come up with something new; old things don’t sell for whatever reason. So new ideas fuel the market and create new needs. And that’s one notion of progress, whereas this utopian rejection of capitalism is this other notion of progress (or a step forward), but both veins keep coming back up and up and up.”

Barry said, “I love also that this definition of utopia as always an unrealized paradise. Within the idea of utopia is dystopia in some way. We as human beings can’t be satisfied. In some ways that makes sense, because what if you just said ‘hey, everything’s cool!’ and stopped working.”

“Smoke weed urry day!” I joked. “Well we did exist for tens of thousands of years …"

“Millions!” Barry interjected.

“ … being perfectly happy with what we had,” I finished.

“Yea, what happened?”

“Some dude coveted his neighbor’s wife, I guess.”