from pastelegram.org, June 2011 – April 2014

I Have Seen the Future: Norman Bel Geddes Designs America

The slogan “I have seen the future” appeared on a pin given to visitors of the Futurama exhibit at General Motors' pavilion for the 1939 World’s Fair and supplies the title for the Norman Bel Geddes retrospective at the Harry Ransom Center. The phrase, which optimistically headlined the Bel Geddes-designed Futurama exhibit in 1939, is also an apt summary of his highly stylized designs for futuristic consumer products, hypothetical architecture and idealized urban plans. Yet more than solely an interpretation of the designs themselves, the phrase presents Futurama and Bel Geddes' work as part of an epic visual spectacle full of optimistic stories of a utopia which—to quote General Motors' 1940 film documenting Futurama—“far from being finished, is hardly yet begun; a world with a future in which all of us are tremendously interested; because that is where we are going to spend the rest of our lives; in a future which can be whatever we propose to make it.” 1

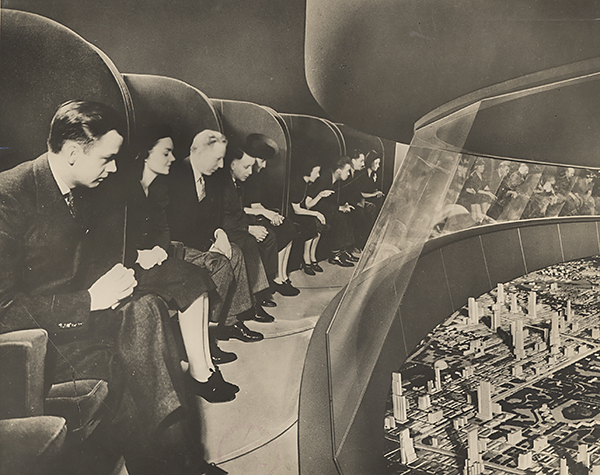

General Motors, Futurama Spectators, ca. 1939. General Motors LLC. Used with permission, GM Media Archives.

The retrospective climaxes with an illustration of Futurama and Bel Geddes’ designs for it, which took visitors on a then-dazzling automated ride around scale models of a fantastic 1960s world. The ride imagined cities designed according to the Modernist urban planning principles of the time: highly-zoned divisions between residential, commercial and industrial areas; cities populated with high-rise residential towers set within bucolic pedestrian parks; and, most importantly for the General Motors-sponsored exhibit itself, a freeway network that connected cities across the country. This exhibit, known for popularizing the idea of a national interstate highway system (authorized under Eisenhower in 1956), is also the grandfather of the “world of tomorrow” industry-sponsored amusement park rides later popularized at Walt Disney's Tomorrowland (opened at Disneyland in 1955) and EPCOT (1982) theme parks. These rides involved elaborate set designs and lofty rhetorical narration that proposed illustrations of an inevitable future in which all the world's problems and frustrations were cured.

Today, such theatrics seem absurd; Matt Groening's Futurama, named after the 1939 exhibit, turns Bel Geddes' bright-eyed wonder world into a surreal farce. If the Futurama exhibit now looks like spectacle, that is in part because such positive visions of the future now seem ludicrously optimistic. It is also because the Ransom Center's retrospective prepares its audience to appreciate the stagecraft of Bel Geddes' work more than the wisdom of the works' ideas.

Though Bel Geddes is most famous as a torchbearer for the streamlined style of Modern product design and architecture popular in the 1930s, in the late 1910s and 1920s, he was widely known as a theater set designer. The exhibition accordingly presents his early work with theater sets and costume design before moving through his product design and architecture. His theater productions, illustrated through his lucid watercolors, charcoal and ink drawings, are graphic and hyper-real. The spectacle of these stage sets resonates with the futuristic pageantry of his later consumer products— radios, telephones, gas ranges, toasters, cocktail shakers, automobiles and airplanes—products emblematic of a new Modern society. The exhibition illustrates these objects in their nature as semi-fictional objects through drawings, photographs and advertisements, as if they were props in an epic theater production about the future.

Francis Bruguière, Divine Comedy Model with Lighting and Figures, 1924; image courtesy of the Edith Lutyens and Norman Bel Geddes Foundation / Harry Ransom Center.

Vandamm Studio, "Travel Smartly in Tweed" window display for Franklin Simon, ca. 1929; image courtesy of the Edith Lutyens and Norman Bel Geddes Foundation / Harry Ransom Center

Highlighting Bel Geddes' seemingly casual shifting between theater, advertising, exhibition design, product design and architecture from the 1920s into the 1940s, the Harry Ransom Center exhibition shows Bel Geddes as blurring the lines between the theater prop and the designed consumer object. In doing so, his designs helped immerse the public in an epic fiction about a bright, positive and Modern future. His lasting legacy is less the ingenuity of his ideas and more the lessons learned about the power of design to engage the public in an optimistic myth of new-ness and progress.

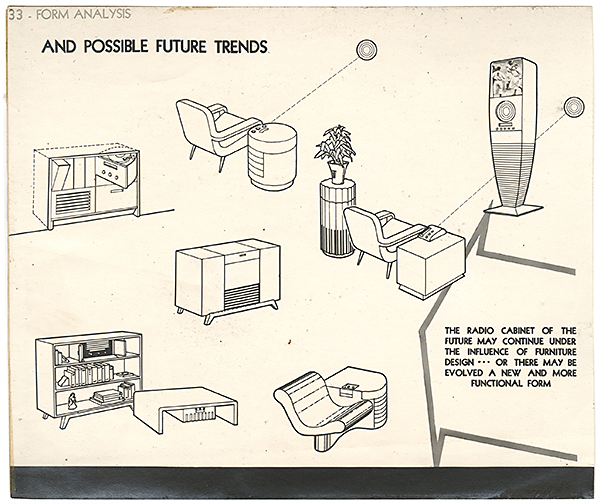

"Possible Future Trends" for radio and phonograph cabinet design in Norman Bel Geddes & Co. "Quarterly Report to R.C.A. Victor Division, Stationary Combinations—Stage 1," ca. 1942—44; image courtesy of the Edith Lutyens and Norman Bel Geddes Foundation / Harry Ransom Center

- 1. The GM video is available at: http://archive.org/details/ToNewHor1940