from pastelegram.org, June 2011 – April 2014

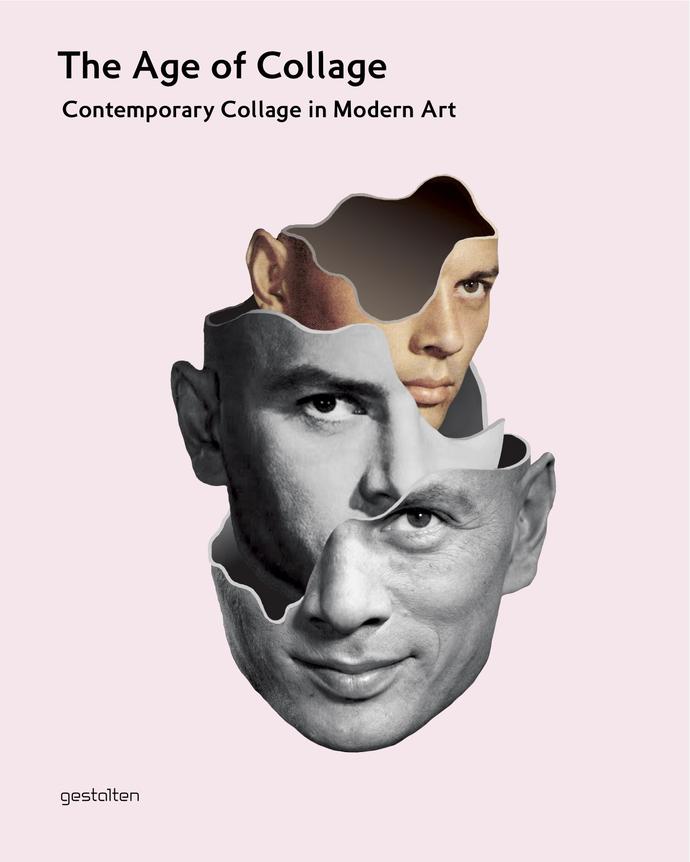

The Age of Collage: Contemporary Collage in Modern Art

In the foreword to The Age of Collage, Silke Krohn distinguishes the collagists of today – both digital cutters and pasters as well as scissor devotees – from their early 20th century forebears. Unlike the Cubists, Dadaists, and Surrealists who centered their practice on common artistic or political goals, today’s collage artists are aggressively disparate. This is in part due to the Internet, where artists can access many more images than ever consumed by their predecessors. Yet it is also more than just a result of an impressionable art form’s expansion in the digital age. This disparity is an antagonistic act—a way of creating something new at a moment when all material seems to be owned by others.

The Age of Collage makes no attempt to give shape to this shapeless medium’s history. An encyclopedia of eighty artists without chapters or groupings, the book’s organization intentionally reflects the diversity of collage over the last several decades. In this presentation, it simultaneously defines and destroys our past and present notions of what collage is and what it is not. Collage, Krohn writes, is everyday life. It is a compilation, quotation, homage or reference and it shows that “the desire to create something new and different from the existing is found everywhere.” The book tries to capture this idea by tossing out any specific organization. Instead of providing a blank slate for the works to stand out, however, such a flat presentation of eighty artists does them a disservice, as if it were an aimless history.

An underlying current throughout the text, though rarely addressed except as something to be forgiven, is the idea of collage as theft. Collage artists steal images from other sources. They take and combine things in unfamiliar ways, disrupting received ideas about originality and the cult of the artist’s imagination. This is one of the most dynamic and challenging things about collage, especially in a digital age. It’s not something that begs an apology. Collage at its core questions the possibility of originality as well as intellectual property and our obsession with the new.

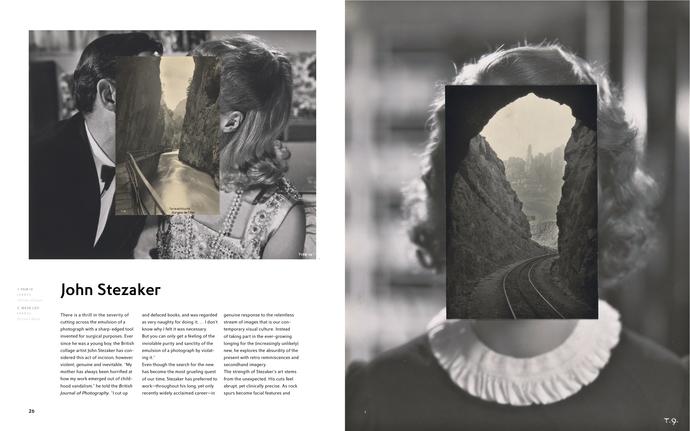

Several artists in the book revel in this sneaky disruption. British artist John Stezaker, for instance, gleefully pursues theft of “secondhand imagery.” For Stezaker, “copyright issues are moot” since all property, especially intellectual, is borrowed. By chopping and dismembering published images and artworks, Stezaker shows a healthy disregard for the original. Rather than putting the past on a pedestal, preserving it in a static state, Stezaker takes it apart to unpack the present—resulting in images that reflect the sometimes-repellent face of modern life.

Other artists in the book, however, reconfigure historical images as a way of holding up a mirror to the present, not merely to disrupt or stick a knife in it, but to admire the way those images cast a pleasing glow. Jesse Treece, for example, draws inspiration from the work of mid-century architects. His method of collage reflects a builder’s eye, layering and constructing worlds from appealingly colored vintage images. His work is nice to look at, which seems like a shallow detail, but beauty is largely absent from The Art of Collage. Treece creates something new from something old without ripping it to shreds. His work is attention-grabbing precisely because of its incongruity with the loud aesthetic of his contemporaries – like seeing a tea party in the middle of a protest.

It raises the question of whether the most novel collage is not actually the one that borrows, steals, and repulses with punk disruption, as the book suggests, but rather the one that lulls you into a dreamy state of nostalgia, sanitizing the past to conceal the messy present.