from pastelegram.org, June 2011 – April 2014

The Duel: An Interview with Andrew Douglas Underwood

Why did you pick the duel between Burr and Hamilton as your subject matter for a project?

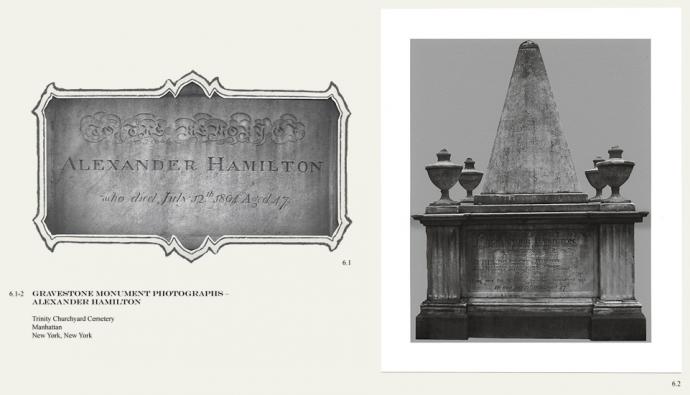

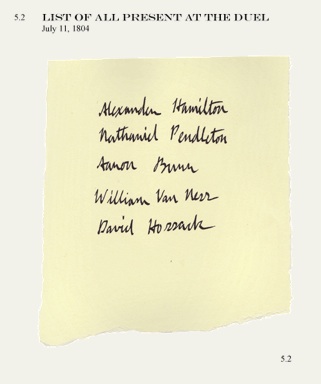

This project began in a pragmatic way. When my wife and I planned a trip to Manhattan I began to search for a content-rich subject that tied in with New York history. Gravestone rubbings and photographs that I made on the trip are included in the project.

Of the many possible projects related to New York the duel caught my attention because it complemented my current direction. There is an intuitive element to my selection process that is difficult to quantify. My projects usually have a generally romantic quality; in this case, the romance is in dying for a belief. That a man would die for his principles, I find compelling and challenging to understand.

Andrew Douglas Underwood, screenshot from At the Weehawken Dueling Ground, July 11, 1804; 2012; image courtesy the artist.

When you say "current direction," how would you describe that direction? In what ways—in terms of content, method or visual aesthetic--do you feel your current project compares with some of your earlier works?

Before I began thinking about my work primarily in terms of content—that is, research into historic phenomena—the context for my work was focused on the medium with research in the background. The last work that I approached this way was a series of paintings borne out of reading Howard Carter’s account of his excavation of King Tutankhamun’s tomb. I painted pages of artifacts. It seemed to me that the next logical step was to create physical archives.

Thinking of my work as research- rather than medium-based allowed me the freedom to make anything that would be effective for the project. What I did was hardly without precedent, but it completely opened up my practice. The archives that I’ve been making could be prints, drawings and small sculpture, but are often collected in customized clamshell boxes. The exhibition of a project can be much larger than what would fit in a box, and I often try to tailor my objects for whatever space I’m exhibiting in. With the project for Pastelegram, space wasn’t an issue. My limits were time and finding a point at which I felt that there were enough materials to give a deeper perspective on the duel and its periphery.

Can you describe your research process for At the Weehawken Dueling Grounds? Where do you look for materials and why did you pick certain objects over others?

List making is an important part of my process. I often begin thinking about a new project by making lists of every possible project that comes to mind. Then I choose the project that makes the most sense for me conceptually and logistically. Then I make another list of possible archive components for the selected project. Finding books usually enters into the process at this point, and I begin reading about the subject. That opens up the possibility for more work that could be included in the archive. At this point I make conscious choices about what will be included and excluded from the project.

Andrew Douglas Underwood, screenshot from At the Weehawken Dueling Ground, July 11, 1804; 2012; image courtesy the artist.

Other artists have depicted the duel. I considered making my own rendering, but I worried that to make something literal in this case could diminish potential engagement with the work. It’s like reading a book and then watching the movie adaptation. The images imagined while reading the book are ephemeral enough that they could be easily overwritten by the literal images depicted in the movie. That’s why I chose to avoid depicting the duel itself. I have tried to provide enough ephemera related to the duel to setup the action in the imagination of anyone trying to envision it.

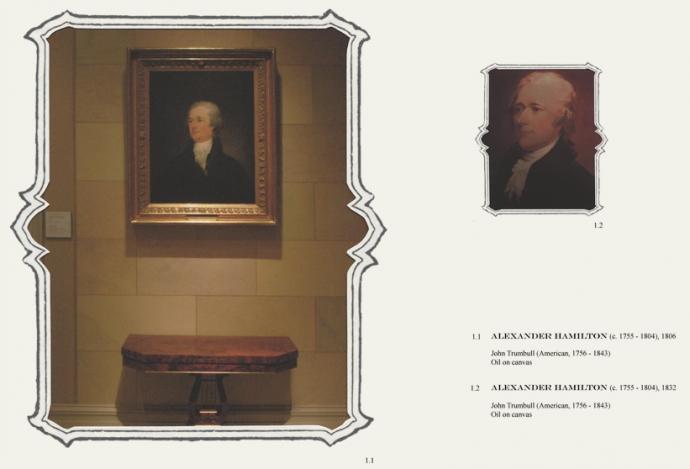

You also mentioned that you began this project, more or less, during your trip to Manhattan with the gravestone rubbings you did there. Since that's the case, why do the gravestone rubbings come at the end of the series of images and texts you created for your online issue of Pastelegram? Why begin with the two paintings of Hamilton?

I arranged the work in this project to evoke the narrative of the duel. At the Weehawken Dueling Grounds, July 11, 1804 begins with a folder, symbolically containing the archive contents. The project proper begins with images of Trumbull’s paintings of Hamilton as in life, moves to the setting of the event, then depictions of items spotlighting items relating to the duel, and the results of the conflict. The last panel is the back of the folder that began the project, completing the circle.

Andrew Douglas Underwood, screenshot from At the Weehawken Dueling Ground, July 11, 1804; 2012; image courtesy the artist.

So you’re bracketing the duel with Hamilton; it begins with him in life and ends with his grave. Why Hamilton instead of Burr?

The duel cast Hamilton as a tragic figure in the sense that he lost. With his death the duel became a defining moment for Hamilton’s legacy, if not the main defining event. It may have been an important moment for Burr, but it didn’t end his life, so to my mind, the event isn’t as significant to Burr’s life and legacy as it is to Hamilton’s.

In developing a sequence for this project a logical progression rose to the surface. Death, love attained and birth are classic storytelling devices used to punctuate the end of a tale. For this narrative, death was the obvious choice. Beginning the sequence with an image of Hamilton alive created a thread that ran through the project.

This article is part of " At the Weehawken Dueling Ground, July 11, 1804,” by Andrew Douglas Underwood. Other parts of this project include:

At the Weehawken Dueling Ground, July 11, 1804 by Andrew Douglas Underwood

The Duel - Source Archive by Andrew Douglas Underwood

Burr by Michael Agresta

On Archives and Absence by Laura A.L. Wellen

and our editor’s statement