from pastelegram.org, June 2011 – April 2014

An interview with Aileen Passloff, on the American Theatre for Poets, Inc. and its surroundings

[…]

Robin Williams Where are you from initially? Where were you born?

Aileen Passloff New York. New York is my home. I was raised in Queens. When I was old enough to ride the trains by myself—which was thirteen—I started going to the School of American Ballet. Climbing up the fire escape to watch the New York City Ballet. It was Jimmy [Waring] who taught me how to climb up the theatre’s fire escape, because we went every night.

Was that when you were thirteen?

Yes.

So you were lifelong friends.

Yes, yes. Indeed we were. […] He was marvelous to me, paid for my first rehearsal studio, and took me home and fed me afterwards. He had no money, but he was extremely generous to many of us; not just to me but also to David Gordon and Valda Setterfield and others. He had broad vision. It didn’t matter whether you were a ballet dancer, or a modern dancer, or an actor, or a writer or a musician. We all worked together.

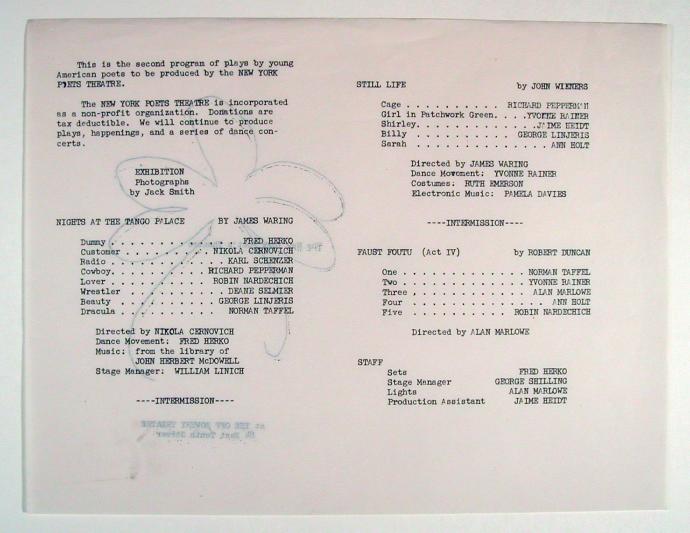

Program, One-Act Plays by James Waring, John Wieners and Robert Duncan,1961-1962; image courtesy the Harry Ransom Center.

I think I read that you took classes from Waring also.

Yes, that was so important for me. He was influenced by John Cage’s chance methods and the I Ching …. But I didn’t know anything about that, I just knew about ballet. It was eye-opening to me to start thinking about rhythmic variations and seeing different kinds of dynamics going on in the body at the same time. It opened a whole world for me.

What were his classes like? I know [Waring] was using chance methods as well as David Vaughan, who you mentioned before, and who described his classes as making dance collage-like. Can you expand on what he maybe meant by that? Or what his process was like?

Well, Jimmy was of course a collage maker. (By the way his collages were part of the exhibition at the Museo Reina Sofia in Madrid.1) We’d come in and take some paper. You’d tear the paper up into thirteen segments, with each piece representing a segment of time within the dance. Then you’d say, “Okay, the first section is two minutes long.” Then you’d divide the rest of the time up by throwing the pieces in the air, using where the pieces fell to determine the time segments for the rest of the dance, ranging from as short as two seconds to much longer.

Then you would throw the pieces again to figure out the dynamics for each segment. You might have the first section all percussive, the second section all lyrical, the third one sustained. But all of this was determined by chance, so all of the sections could end up being percussive, if that’s how the papers fell.

And then you would throw the papers a third time to establish which body part would be doing the action for each section. Maybe you’d end up with sixteen percussive moves in one second with your feet, while your head did something lyrical that was only one gesture. The dances were not naturalistic but made one look at things in a different way. I guess what struck me so much is the broadness of his vision; that there was no prejudice. I’ll tell you a microscopic story, which is a Jimmy story:

We all used to hang out at the Automat, which was near the School of American Ballet. I’d do my homework there and we’d talk about rehearsals, figure the costumes out and all kind of things—because you could sit there all day long and they’d never tell you to move. Jimmy got up and said, “I’m going to get something, do you want me to bring you something back to the table to eat?”

And I said, “No, thank you.”

He asked, “Wouldn’t you like some Jello?”

I said, “No thank you Jimmy.”

He said, “Why not?”

I answered, “Because I don’t like Jello.”

And he said, “Why not?”

And I said, “Because it shakes.”

And he replied, “That’s prejudice,” and brought me back some Jello. I never forgot that as long as I live, and I was thirteen or fourteen years old at the time. It was that idea of being open to anything.

Is it like making your experiences more concrete before passing judgment?

Not quite. It’s the work that dictates the process and what you use. If you listen to the work, you’ll find out what it needs. That point of view came out of Jimmy’s teachings, although he never explicitly said that, it is something I learned from him.

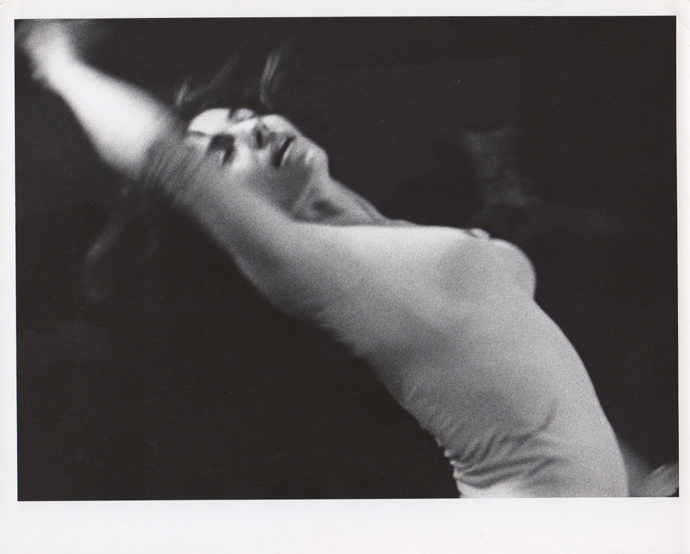

Unidentified photographer, Aileen Passloff dancing, c. 1960s; image courtesy Aileen Passloff.

Was it also Waring who led you into the theater? Because I know you were not only involved in dance but also involved in theater.

Absolutely. We were working at the Living Theatre in the beginning. Now my chronology, I don’t trust it very much, but I am going to dig out some programs and get the chronology more definite. That was where Julian Beck and Judith Malina were doing such strong work in theater at that time. But Frank O’Hara was also there, so we were working on some of his plays. I was doing classical work like Yeats’ Full Moon in March, which I did with Larry Kornfeld. A little bit later Merce Cunningham began teaching at the Living Theatre. It was a center for all of us. This was prior to Judson. Of course the dancers you would see in all those little theaters the Maidman, the Gramercy Arts, the Cubiculo and many others. Loved it, it was wonderful to play with those balconies and staircases and places that made different kinds of things happen. For example, Allan Kaprow wasn’t part of Dance Associates2, but the Happenings people were around. I worked with Richard Foreman, and Kaprow, Claes Oldenburg made costumes for me. I had music from La Monte Young, it was Chair Music that he gave to me. There was a huge amount of collaboration going on between all of us and Jimmy wrote music too.

[…]

So if we can talk a little bit about the New York Poets Theatre and the kind of work you were doing there. I know you participated in many plays, you acted and directed and so forth. Can you just talk a little bit about the creative process, if that can be typified in preparing the work for the Poets Theatre?

I was scared stiff. I started choreographing because Jimmy said to me, “Well who else do you think is going to choreograph for you?” I thought that over and didn’t see people lining up to do that, and so I thought I better get to it. The same thing with directing, I thought, “Oh goodness I don’t know how to do that,” and Jimmy pushed me to begin. I would also audition for things because I thought it was good experience to hear what people wanted, what they needed. And I kept waiting for the director to tell you what to do and I realized then that the director doesn’t tell you what to do. I would stay in the theater for many hours when it was empty and start to think about what was important to me in theater. Many of the things I developed alone in the theater at night are things that I still teach.

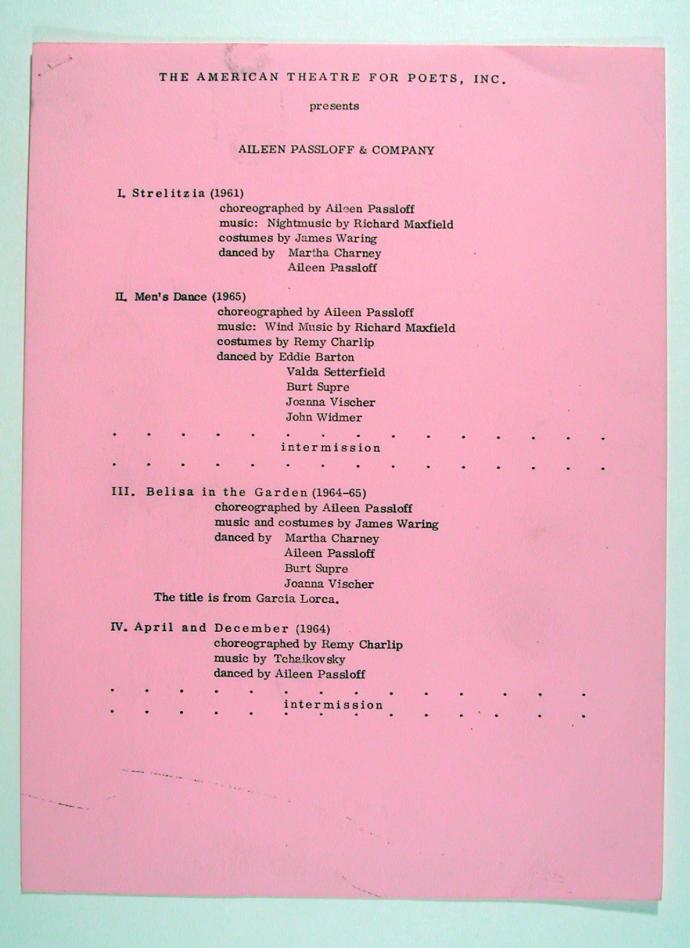

Program, Aileen Passloff and Company, 1965; image courtesy the Harry Ransom Center.

[…]

So I’m curious to go back to the Poets Theatre. You say you were directed in that way toward the theater in part because of your friendship with Jimmy Waring. Were you already interested in poetry or drama, or did it come more out of your relationship in that community?

It came out of dancing. Really everything came out of dancing. I didn’t know anything about poetry, I read it, I loved listening to it, but I was ignorant. So it wasn’t that. The idea of making events happen, of making life always interested me, whether it was teaching or making a choreography or making a play.

You think of that as making life? What do you mean by that?

It’s like there isn’t anything there before you get this white paper. Nothing’s happened and you make the first marks on it, so it’s the beginning of something that’s alive, which is endlessly interesting.

[…]

Do you have a sense of the audience at the Poets Theater? Was it a small community of interested artists or did you have a larger public at all?

I don’t know if I trust my memory, but I think I do. When we would go to see something or you would recognize everybody in the audience whether it you went to hear Jackson Mac Low read poetry or whether you were seeing a new work by Jimmy Waring or hearing new music by Richard Maxfield or La Monte Young or whatever it was. Maybe you didn’t know their names, but you knew their faces. So we all went to everything, there wasn’t that, “Oh, I’m an actor therefore I don’t go to see dancing.”

Can I ask you a little bit about your dance company, Aileen Passloff and Company? The company you had between 1958 – 1968, which is a time when obviously huge changes are happening in dance. Can you describe the kind of work that you were making and your company presented? What was it like? What were you trying to achieve?

Of course I’m talking about it now from many years later. Fifty years later, practically. I was interested in heat. I was interested in the dancers seeing each other and focusing on what things felt like. To take action, what did that feel like? What did it feel like to be close or far away? So I insisted on people really experiencing their own action, not just indicating it. So even though my training was very much about skills—and I’m all for skills—it wasn’t the skills that interested me so much on stage. I wanted the dancers to look out from their own experience, whether they’re falling or holding each other or even sitting next to each other. For me that’s a deeply human experience; the work was abstract, there were no narratives. I got interested in scale and layering. In one of those productions—at the Gramercy Arts—I remember putting dancers on the theater balcony. I had found a staircase behind the theatre’s cyclorama, and by taking down the cyclorama I revealed the staircase as part of the stage. I placed the lighting man under the staircase, so you saw the lighting man, you saw the staircase, you saw the balcony, you saw all these layers of life…

So you’re exposing the background—

Underbelly.

Unidentified photographer, Aileen Passloff dancing, c. 1960s; image courtesy Aileen Passloff.

[…]

Thinking about the field of dance at the time, during the period of your company, or during your period of work with Judson Dance Theater, how do you think your approach or your dance differed from others?

The work that I did was romantic sometimes. I think of it as heavily perfumed, it had that sense of thick atmosphere. I loved the work that was around me, like that of Yvonne [Rainer], which was so different that I felt changed from seeing her work. Sometimes people described what I did—for example, Allen Hughes3 of The New York Times said, “leader of the avant-garde in the looking backwards approach.” I dared to do whatever I dreamt of. I had a most remarkable company. They were passionate and they were really connected with each other. I don’t mean we were friends as such, but we sure knew how to work with each other.

You were working with wonderful dancers.

I was so lucky. I worked with Joan Baker, at one point I made a piece for Yvonne Rainer and Lucinda Childs called Bench Dance. I had David Gordon and Valda Setterfield. I had Jerry Martin, Martha Jane Charney, Joanna Visher (who had been with Balanchine), Toby Armour. I had divine people to work with. Beautiful Vincent Warren who went on to work in Canada. The actor and dancer Bill Maloney from Herbert Berghof Studios worked with us also. Also a lot of us were studying with Antony Tudor. They were all from widely-varied backgrounds but all with a deep musicality.

You described your work as having a thick atmosphere in contrast to Yvonne Rainer. Her work is obviously bare and minimalist. Did you retain a lot of musicality or balletic quality?

Musicality, for sure. I don’t think what I did was balletic, but I do think it had a dense atmosphere. Yvonne had a different atmosphere, though.

Where did the dense atmosphere come from?

In some cases, it came from the rich music we worked with, which created the atmosphere—

Like Richard Maxfield?

Yes, his work is gorgeous. Jimmy’s work was hugely atmospheric. I think mine was something like that. Sometimes people seeing my work might think, “Why are they jumping rope in this place?” or, “Where does a tap dancer come in?” Because I would have somebody doing tap or somebody doing a gun drill with umbrellas. In one way those things might have looked arbitrary. But it was because all kind of movements interested me.

What were you wearing?

Well, it was different. I was lucky enough to have many fine artists collaborating with me on costumes, primarily Waring and Claes Oldenburg. The costumes for Strelitzia—the ones that are now at the Reina Sofia which were made by Waring—they came from an evening dress that I found in a thrift shop and cut it in half. Half went to Barbara Lloyd and half went to me. Jimmy made tops from old sheets and gloves he’d found. There were shoelaces that he put in a little gauze bag, and a piece of fur that he put on the sheets. And he put lavender lace and antennae on our heads. Oldenburg did bold works, he put us in stripes and brilliant colors. For Arena he put numbers on our backs. I put together the costumes for Salute to the New York World’s Fair, which was at The Gramercy Arts. My memory is that Martha Jane Charney wore little black velvet skating trunks and tap shoes. Maybe there would be a big number on your back or something like that. They were bold. Other artists would be around the studio … Fay Lansner made costumes for me also. So there were artists around. And there were other artists around my studio, like Mark di Suvero, so we had amazing painters and sculptors around us. Oldenburg at that time was creating The Store and he needed dancers behind curtains. The performances at The Store made it seem as if you were at a peep show, as if you were seeing something that maybe you shouldn’t see. Allan Kaprow and Richard Foreman both wanted dancers to perform in their work. There was a community, you know, and so we all did whatever needed to get done. I was game for whatever; I just figured, “Let’s do it and see what happens.”

So a sort of fluidity in terms of collaborations with you as a dancer, Oldenburg as a visual artist…

His wife Pat [now Patty Mucha] was taking my dance class. She is a wonderful woman. Claes didn’t know how to sew, so we would buy some cheap fabric and he’d tear it with his bare hands. And she’d pin it and squoosh it together and it would become marvelous. And Remy Charlip was doing posters for us. Even though each of those people were remarkable in their own right, there was oddly enough little ego at play. Perhaps that was because nobody had any money. Nobody was looking at work in order to succeed at that point. They were aiming to make something that was beautiful and that might have meaning. That made for our sense of community, but it’s odd to because most of us weren’t friends outside of rehearsals. We came, we did the work and we left, but we worked very deeply with each other.

Since you’re coming from a classical ballet background, how were you thinking about your work and that of other innovative dancers and choreographers at the time in relation to the then standard bearers of the time, like George Balanchine and Martha Graham?

I never compared myself to them, I was doing my own work with the people I loved to work with. I was interested in the samenesses and differences of people. Even nowadays my work looks different from what other people are doing, but my work keeps changing. I loved the work of Balanchine—it was his work that I climbed up the fire escape to go see. I also loved the work of Yvonne Rainer, a totally different kettle of fish. But I didn’t feel like I could possibly be like them. It’s impossible. I could only do my own work. I think making a dance is a lot like the process of making a sculpture, you look to see what’s inside of a stone or a piece of wood and you try to reveal it. You listen to it until you can understand what’s happening inside. That’s the process that always fascinated me. It didn’t feel like I was the main creator, but rather I was the servant of what was already there. It wasn’t about me, it was about the work. I was the person who was looking and listening.

[…]

How important was the anti-war movement to the content of the theater production?

Tremendously important. At the Living Theatre they were doing The Brig at the time that we were doing classical work. Fierce, strong work. They were testing all the limits. And confronting the audience was new at that time whether it was during the performance or in the lobby at the intermission. They engaged in nose-to-nose confrontations with an audience member because they wanted to change our consciousness. Much of that made me uncomfortable, in truth, because I was shy and conservative girl in one way and fiercely individual in another way. I was uncomfortable but I admired their testing of the boundaries. Should we wear make up, should we wear costumes, should the audience have the protection of distance from the actors? They did away with that protection; they practically sat in the audience’s lap. Those were boundaries that everybody was testing. How far should we go, should we do these performances in the street, where does theatre happen and where should theatre happen? Really, we were testing the rigidity of the limits, if the limits can be or should be broken.

Unidentified photographer, Aileen Passloff dancing, c. 1960s; image courtesy Aileen Passloff.

Like life. Well, I don’t want to keep you forever.

I think it’s important somehow that this history be known because you can’t recreate that time—it was a time of revolution. We were all recovering from McCarthyism, so it was a fierce time. Things had to change. It wasn’t that it was a nice idea to test ideas. We were questioning everything, whether it was the role of women or the distance between the performer and the audience or the role the government has on our lives. Or what do we think about drugs, what do we think about sex. So many questions came up and urgently needed to be dealt with; that is perhaps what led to our sense of community in that it was what we all had in common. It was a time of idealism.

But it was also a dangerous time. It was intolerable where we were, we had to take risks, to make a move, to test things, because of the way things were. We couldn’t accept being quiet anymore. So it wasn’t an intellectual idea, it was visceral. So there was this incredible community and productivity; but this energy also came with a darker undercurrent of danger and fear. People tested the limits and took risks and some disintegrated. So we were living in a time when you prayed that the people you knew would be alive the next day. But at the same time there was an extraordinary sense of community and what anybody needed you helped them to make it happen. All of us worked together to reach for something that was truthful or beautiful, and that’s what made it so exciting.

This article is part of "There Is No Taste in Theatre: It is a Medium," edited by Chelsea Weathers. Other parts of this project include:

A Partial Index of the American Theatre for Poets, Inc., 1961–1965

Creating Context by Chelsea Weathers

Theatre Quote Unquote:* The Expansive Gestures of the New York Poets Theatre (American Theatre for Poets, Inc.) by Leanne Gilbertson

Reading Frank O’Hara’s Loves Labor: an eclogue, an elegy for the New York Poets Theatre by Cameron Williams

and our Editor's Statement

- 1. Robinson, Julia and Christian Xatrec, curators. ± I96I: Founding the Expanded Arts (Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte: Reina Sofia). Exhibition June 19 – October 28, 2013.

- 2. A cooperative of choreographers started by Waring and other dancers in 1951.

- 3. Allen Hughes was an important dance critic for The New York Times during this era.