from pastelegram.org, June 2011 – April 2014

Theatre Quote Unquote:* The Expansive Gestures of the New York Poets Theatre (American Theatre for Poets, Inc.)

And so from the start the theatre was the place where almost anything could happen, where the most unlikely events could be made solid, made flesh, and taken to their amazing conclusions.

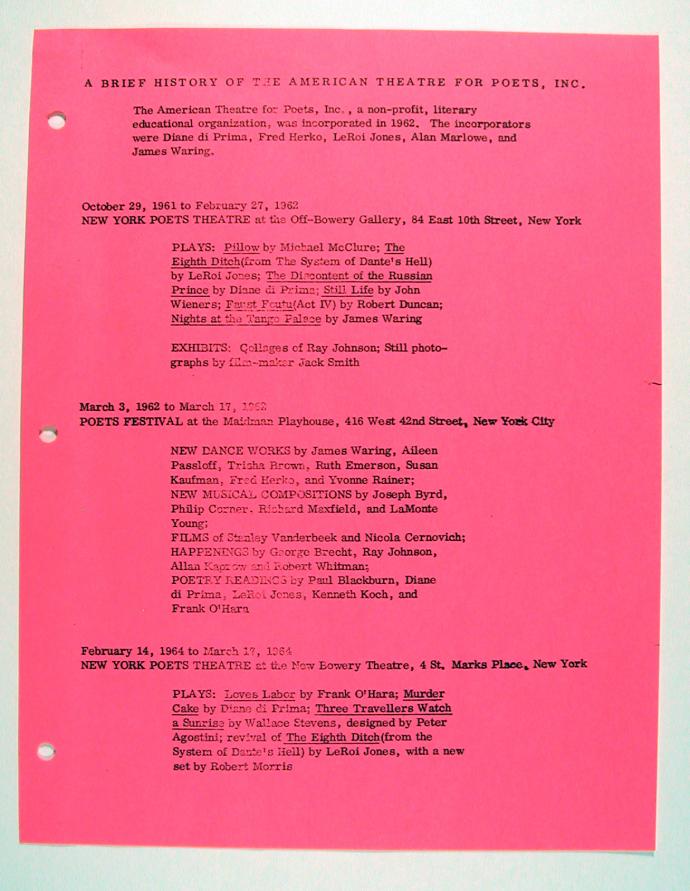

In fall 1961, the sometime stage manager and poet Diane di Prima, the choreographer James Waring, the playwright and poet LeRoi Jones (later Amiri Baraka), the dancer and choreographer Fred Herko and the model and actor Alan Marlowe, decided to form an ad-hoc production company known as the New York Poets Theatre. In January 1962 the company was incorporated as the American Theatre for Poets.2 The Theatre would be sporadically active for the following four years at various venues and under various names.

Di Prima’s notion of the utopic and transformative potentials of “theatre” mobilized the young poet’s involvement in the Living Theatre in the 1950s and her later participation in forming the New York Poets Theatre. She derived her particular sense of “theatre” from watching and managing performances that emphasized distilled, emblematic images and abstract characters rather than linear narratives and psychological characterizations. Such performances embraced an open-ended collaborative approach to production and rejected the hierarchical power structures of commercial theatre. Formative, too, was her familiarity with Black Mountain College. The school’s cross-disciplinary artistic experiments, such as John Cage’s “Theater Piece” (1952), as well as the work of its poets Charles Olson and Robert Creeley, celebrated the detritus and slang of American popular culture as source material in an attempt to blur the line between art and everyday life.

Di Prima had also come to know figures from various artistic backgrounds including several students (Herko, Yvonne Rainer, Valda Setterfield, Aileen Passloff, among others) who danced with Waring and/or had taken, along with di Prima, his influential experimental dance composition class at the Living Theatre. Also among di Prima’s acquaintances at the time were the experimental composer John Herbert McDowell; lighting directors Nicola Cernovich and William Linich (now known as Billy Name); the poets Allen Ginsberg, Frank O’Hara, John Wieners and Lawrence Ferlinghetti; and the artists Ray Johnson and Allan Kaprow. This richly networked environment was one in which experimental film, “the art world, the worlds of jazz, of modern classical music, of painting and poetry and dance, were all interconnected.” Such fertile creative grounds fed di Prima’s desire to form a theatre in which “John’s music, Jimmy’s choreography and plays, Freddie’s dance, my own and LeRoi’s plays, all would have a place,” and which would allow Marlowe to direct and manage the fund-raising.3 Di Prima hoped to create a place where a diverse group of creative individuals and their divergent artistic talents and preoccupations might find a sense of belonging and meaning; some temporary home.

Di Prima’s account of the birth of the Poets Theatre suggests it was to be a generous community where different artistic media and various artistic visions might all find their place in the world. In this sense, the Theatre was to serve as a platform for experimentation. Its unresolved and perhaps unresolvable nature in the next few years offered a horizon of potentiality along which could be mapped a variety of radical inventions and transformative moments. These ranged from a haunting ritualistic dance by Freddie Herko for a recently-deceased friend to an early concert by the rock band The Fugs; from the premiere of dances by several figures associated with the Judson choreographers who would later be considered founders of postmodern dance to Happenings by Allan Kaprow and George Brecht; from readings by William Burroughs to a night of Blues singers that included Muddy Waters and Sonny Lee Williams. The contribution of these experiments to the evolution of intermedia and interdisciplinary experimentation—and by extension to an expanded creative network that extends from the 1960s to now—remains somewhat under-investigated. This oversight seems in part a result of the Theatre’s ad-hoc nature and goal of inclusiveness, which, like much of the artistic experimentation of the 1960s, does not easily lend itself to commercial success or museumification. Since the willfully disparate aesthetic of the Theatre tended to favor collage-like constructions, this also thwarts easy disciplinary and stylistic categorization. This preference is witnessed in the design and contents of many of the Theatre’s programs, materials and productions. For instance, in March 1962, a “Poets Festival” was held at the Maidman Playhouse that included new dance works and musical compositions along with films, Happenings and poetry readings. The list of participants reads somewhat like a “Who’s Who” of that moment’s New York avant-garde.

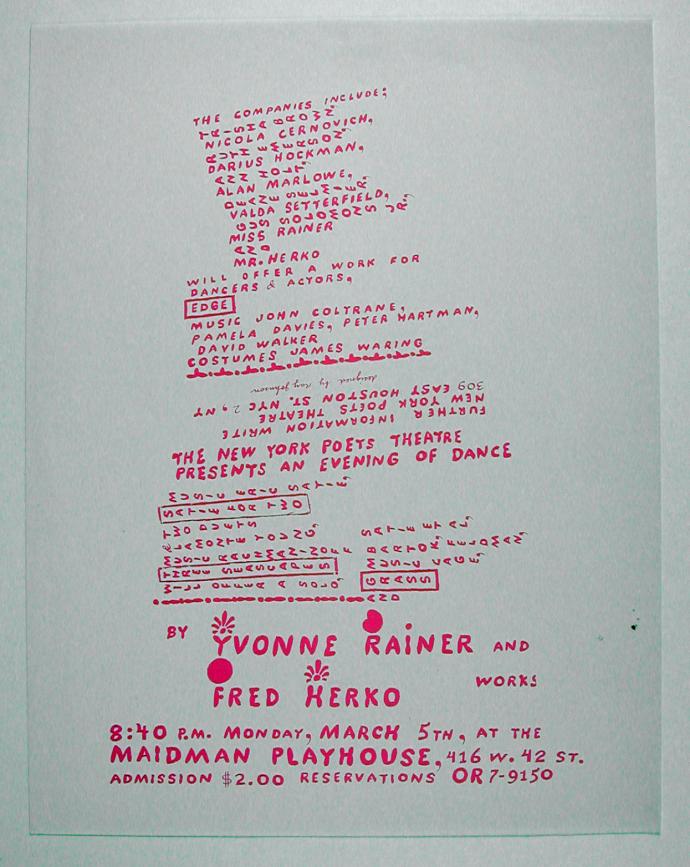

One of the most visually striking programs from this “Festival” was designed by Ray Johnson for an “Evening of Dance,” featuring new works by Fred Herko and Yvonne Rainer and their companies-of-sorts (figures now most commonly associated with the Judson Dance Theatre).4 Johnson’s activities in the Poets Theatre extended beyond this isolated example; his collages appeared also in a solo art exhibition organized in conjunction with the premiere of the New York Poets Theatre at the Off-Bowery Gallery in October 1961, he participated in a "Variety evening" at the Maidman Playhouse in conjunction with the “Poets Festival” in March 1962 and his works were included in a group assemblage exhibition at the New Bowery Theatre in the spring of 1964. Johnson’s disorienting and playfully arranged program makes it difficult to discern more meaningful from less meaningful information, more important from less important participants (aside perhaps from the event’s location and date and the foregrounding of Rainer’s and Herko’s names). His design is similar to the Neo-Dada non-logic of many of the early theatrical productions of the company, which were often constructed by juxtaposing words and characters with an indifferent-to-logic use of movement and imagery.

The program’s design signals something of what scholar José Esteban Muñoz has characterized as Johnson’s radically democratic point about “everything corresponding to everything,” a point the Theatre also makes in its founding concept and actualization.5 The insistence in Johnson’s design on fluid interchangeability and dissolving aesthetic value also echoes di Prima’s longing for and creation of a theatre “where anything might happen.” The open-endedness of Johnson’s program—and of much of the Theatre’s activities—also links them thematically and affectively to the emergence of a queer aesthetic and social world. This queerness manifested itself not merely at the level of sexuality, although the environment surrounding the Theatre sustained experimental modes of love, sex and relationality. The queerness I discern emerging at the Theatre linked the typically separate spheres of making work and living life and was characterized by a rejection of natural orders, definitions, hierarchies and directives as well as by an embrace of ludic invention.

So while di Prima’s account of her experience, with which I opened this essay and which I rely upon for some factual information about the Theatre’s evolution, should not be mistaken for The History of the Theatre, her insights and documented memories do offer a textual chronology of the Theatre’s development, and provide significant insight into how the Theatre participated in shaping such a queer avant-garde social world and aesthetic.6 Notably, the New York Poets Theatre/American Theatre for Poets cannot be credited with founding any one aesthetic—unlike the Judson Dance Theatre, which has become understood as originating postmodern dance—despite the fact that both organizations shared many participants, performances and preoccupations. Many of the productions and experiments staged by the New York Poets Theatre found their original realizations elsewhere and were restaged, reperformed or rescreened in one of its venues. What the Theatre seemed particularly well-suited for was fostering experimentation by artists in various media, some who eventually found their “serious” art careers elsewhere and others who remain relatively unknown. Its expansive and flexible definition of “theatre” and its ongoing transformations and evolutions aided in creating a milieu tight enough to afford a stimulating exchange of influences from various artistic disciplines along with a sense of social cohesion, and loose enough not to constrict personal ambitions. Thus the activities of the Theatre might best be understood as gestures, signaling a refusal of a certain kind of closure and finitude that echoes the queerness of the New York avant-garde at this moment.7

Such queerness seems aptly descriptive of the social world surrounding the Theatre, which consisted of several close-knit relationships, including romantic ones, and which was permissive enough to tolerate if not fully embrace a single mother, a contractual marriage of a woman and a seemingly gay man and an interracial affair, while harboring abiding friendships between many men and women of a range of flexible sexual orientations and couplings.8 Furthermore, the Poets Theatre offered a situation that supported a multi-generational group of creators. Their combined experiences bridged the historical gap, both aesthetically and socially, between a pre-WWII Bohemian avant-garde that often covertly sustained non-normative relationships and a post-WWII queer avant-garde that actively rejected normal notions of love and of life, generally. This carried over into the Theatre’s programming. Works from earlier in the twentieth century with which the participants felt a kinship, like those of Wallace Stevens and Gertrude Stein, were often programmed alongside new or restaged productions of more recent works by figures such as Frank O’Hara, LeRoi Jones and Kenneth Koch. Not only did the inclusion of works by the pre-WWII avant-garde—along with essays on the history of the procedures of the avant-garde in several of its programs9—aid in the Theatre’s goals as a non-profit literary educational organization but this move also suggests how those who worked with or at the Theatre borrowed from and reworked the past to contextualize their own work. Such contextualization gave the Theatre and its creators meaning and significance at a time when it received little critical attention.10 The collegiality and sense of belonging, with those of one’s own generation and beyond, if even only fleeting and punctuated by fallings-out and infighting, sustained not only significant artistic experimentation but also non-normative desires and modes of navigating the world, without prescribing any one orientation or demanding defined relationships.

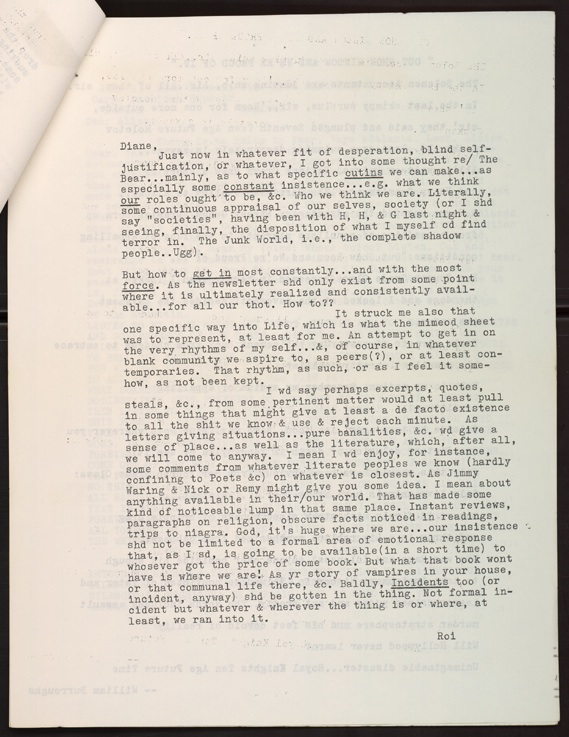

This understanding of the Theatre as creating a place for a community where none previously existed also relates to the experience of reading The Floating Bear, a mimeographed poetry and arts journal published throughout the years of the existence of the Theatre and onwards until 1969. Launched in February 1961 by LeRoi Jones and Diane di Prima, The Floating Bear serves as a material backdrop for the real-time ephemeral performances of the Theatre.11 Mailed to people that di Prima and Jones thought mattered “in poetry, music, dance, theatre, and such,”12 The Bear included writings of all sorts and forms by composers, poets, artists, choreographers, playwrights and critics. A partial list of its contributors from 1961–65 includes George Brecht, Ray Johnson, Edwin Denby, Allan Kaprow, Yvonne Rainer, Jack Smith, James Waring and Marian Zazeela; and during this time William Linich and John Wieners also served as guest editors. The Bear is filled with typographic experiments (as in the Dadaist and Surrealist journals that preceded it) and like the Theatre it articulates inclusiveness, permissiveness, a utopian impulse of collaboration and radical invention. The intertextuality that characterizes the journal, which di Prima has described as “a kind of sixth sense of who was actually speaking to whom in a poem, a review, or article,”13 helps in thinking about the productions and activities of the Theatre and how this publication supplemented the live performances. The Bear recorded and participated in creating a circuit of queer cross-associations and influences that the Theatre enacted.

The editorial vision of The Bear during the years it was being published alongside the Theatre’s productions might best be summed up in a letter from LeRoi Jones to his partner Diane di Prima. Published in issue 5 (April 1961) and reproduced in its entirety below, the letter expresses Jones’s desire for a publication where “all our thot” might be realized and available, a publication that could “get in on the rhythms of my self . . .&, of course, in whatever blank community we aspire to, as peers (?), or at least contemporaries. . . .” His hopes for The Bear are strikingly similar to di Prima’s hopes for the Theatre. Indeed Jones’s choice not to name this “blank community we aspire to” is telling. The insistent longing that Jones expressed in the form and content of the letter is for a place, which could be felt—lived and sensed—but not entirely known or named. That place is one that Jones hoped the immediacy of the mimeographed newsletter could at least partially record, but which he felt formal writing would never capture. It is, in Jones’s emphatic proclamation: “where we are!”

The story of the Poets Theatre’s dissolution is nearly as difficult to synthesize and narrate as the story of its beginning. One issue seems that the experiment was historically and conceptually positioned between a rather serious-minded older generation of artists and a new hip, witty and urbane New York culture, which understood the inevitability of art’s necessity to acknowledge, if only ironically, its inter-relationship with business. Another issue was the imminent alignment of certain participants and their work with the identity politics of the Feminist Art Movement, Gay Liberation and the Black Arts Movement. In this environment, the expansive gestures of the Theatre seemed destined to fail or burn out—to lose their precarious ground. And it is perhaps because of this inevitable failure that I am most intrigued by the Theatre’s life and afterlife, its utopic longings for place-making, which served a crucial role in the emergence of a queer avant-garde and which may still resonate with some inter-disciplinary artistic experiments today.

* Jill Johnston wrote an essay outlining her memories of “dancing” in the 1960s titled “Dance Quote Unquote.” I am borrowing the notion of quote unquote in my title for its suggestion of refusing a certain kind of final definition. It seems quite applicable to how the New York Poets Theatre understood and experienced “theatre.” 14

This article is part of "There Is No Taste in Theatre: It is a Medium," edited by Chelsea Weathers. Other parts of this project include:

A Partial Index of the American Theatre for Poets, Inc., 1961–1965

Creating Context by Chelsea Weathers

An interview with Aileen Passloff by Robin Williams

Reading Frank O’Hara’s Loves Labor: an eclogue, an elegy for the New York Poets Theatre by Cameron Williams

and our editor's statement

- 1. In her memoirs, di Prima goes on to isolate specific moments which shaped this perception of theatrical possibility—watching a performance of a play by Picasso called Desire Caught by the Tail (written in 1941), which she noted was full of weird choreography when it was performed by the Living Theatre in 1952, along with her attendance a year or two later at the Living Theatre’s performance of a version of Cocteau’s one-act play Orpheus (written in 1925 and originally produced in 1926), after which Julian Beck invited the entire audience to his house. Diane di Prima, Recollections of My Life as a Woman: the New York Years (New York: Viking Penguin, 2001): 145.

- 2. In various accounts of the initial formation of the company other figures mentioned include the lighting director and aspiring director and filmmaker, Nick (Nicola) Cernovitch (who had been at Black Mountain College along with another NYPT associate, Ray Johnson), and the composer John Herbert McDowell. While it is possible both Cernovitch and McDowell may have been involved in its conception and were active in many of the productions, the incorporation letter for the Theatre along with many of the announcements, programs and the prospectus (1964) list these five figures as the founders. My thanks to Gerard Forde for sharing a copy of the certificate of incorporation for the American Theater for Poets from Box 6, Diane di Prima Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Library. See di Prima, 255 and Stephen J. Bottoms, Playing Underground: A Critical History of the 1960s Off-Off Broadway Movement (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2004): 62. In 1965 the company, shortly before its complete dissolution, became a members-only club, the American Arts Project, to side-step an elevation of policing of the arts in New York City.

- 3. Di Prima, 186, 256.

- 4. There is significant cross-over among figures and aesthetics in both the Judson Poets’ Theater (which had also began a series of one-act plays in 1961) and Judson Dance Theater (founded in 1962) with the New York Poets Theatre that falls beyond the scope of this essay but that merits further attention.

- 5. José Esteban Muñoz has characterized Johnson’s aesthetic in these terms and written about Johnson’s work in relation to what he calls an “emergent queer postmodernism” of the period. For more information, see Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York and London: New York University Press, 2009): 121.

- 6. As the primary administrator and record-keeper of the operations (named officially as the “Secretary/Treasurer”), di Prima’s biases and any misrepresentations have taken on some centrality in the minimal scholarship that exists on the Theatre. She has noted the gendered division of labor among her cohort as typical of that time in her memoir. While I do not want to exclusively privilege one account of the Theatre at the expense of all others, I find her recollections use a language that resonates most closely with what I have come to understand of the Theatre at this historical moment.

- 7. Muñoz has proposed that many of the creations, performances and activities of the New York avant-garde during this period might best be understood as “gestures” that defy easy definition and signal queerness. Cruising, 65–67.

- 8. Di Prima who describes her first real love affair in her memoir as having been with a woman was a working single mother during many years of the Theatre’s operation and was also, during the later years of its operation, married to Alan Marlowe, with whom Fred Herko (a close friend of di Prima’s) previously had a serious long-term relationship. Marlowe’s and di Prima’s marriage was largely one of contractual convenience rather than romantic love, according to di Prima. Jones (now Baraka) and di Prima also had an inter-racial affair during the years the Theatre was active and while Jones was married. Jones fathered di Prima’s second child Dominique. Despite the relative sexual freedoms and creative opportunities afforded di Prima during these years, she has also noted the substantial strains of being a woman in a male-dominated queer artistic world, including the challenges of choosing to become a single mother. The paradox of a sense of possibility and stifling limitation that di Prima expresses seems typical for other female artists working at the time and merits additional investigation. See di Prima, Recollections.

- 9. For example in a program from 1965, Camille Gordon contributed an essay entitled “Musique Concrete and Chance Theatre” that links the New York artistic activities of the 1950s and 1960s to the activities of the Futurists, through the experiments at Black Mountain College, to examples of chance theatre realized at the Living Theatre, to Happenings and lastly to some of the productions at the New York Poets Theatre/American Theatre for Poets, Inc. Box 1, Folder 7, New York Poets Theatre Collection, Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin.

- 10. Notably, many of the figures who were associated in some way or another with the New York Poets Theatre, such as Diane di Prima, James Waring and Fred Herko, often wrote some of the only existing criticism of the Theatre’s productions, which was often published in The Floating Bear, a publication edited by di Prima and LeRoi Jones. Other reviewers included Jill Johnston whose insightful criticism mainly focused on dance performances sponsored by the Theatre and appeared in her Village Voice column from 1962–65. Tellingly, the primary press coverage of the Theatre’s activities centered around its run-ins with the law. For a review of the crack-down on the arts in 1964, see Diane di Prima, “Embattled Artists,” The Nation, May 4, 1964, 463–65.

- 11. Di Prima’s account of the newsletter’s formation credits LeRoi Jones with the original plan. For more about The Bear, see Recollections, 244, 253–4.

- 12. Ibid., 244.

- 13. Ibid., 254.

- 14. See “Dance Quote Unquote,” in Sally Banes, ed., Reinventing Dance in the 1960s: Everything Was Possible (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003): 98–104.