from pastelegram.org, June 2011 – April 2014

Reading Frank O’Hara’s Loves Labor: an eclogue, an elegy for the New York Poets Theatre

Frank O’Hara, author of the ubiquitous Lunch Poems and celebrated as one of his city’s and time’s best advertisers, also penned a small number of relatively obscure plays. Although they do not circulate widely today, some of these plays were staged during his lifetime as outré events of the downtown arts scene. One, Loves Labor: an Eclogue, was written in 1955 and produced in 1959 by the Living Theater and by the New York Poets Theatre in the spring of 1964. The play borrows the classical poetic form of the eclogue; opening on a pastoral scene of a shepherd and his sheep, the play initially adheres to convention only to break it via a series of interruptions into the peaceful tableau. A barrage of characters—Venus, Irish Film Star, Nurse, Alsatian Guide, Cub Reporter, Metternich, Juno, Paris and Minerva—intrude upon the scene and rupture the eclogue’s historic unity. The characters' disjunctive declamations exist uneasily somewhere between monologue and dialogue. This and these characters’ inherent anachronism establish variety and interruption as the play’s ethos and method. Essentially without plot, Loves Labor demands to be embedded in disparate narratives that exist external to the play and vary according to each character’s evocations. Venus, for example, evokes an ancient cult of beauty while the Film Star evokes a modern one. Each name stands for a different narrative: the play is essentially a series of citations. These knowing winks attract the audience, yet often the obscurity of their referential gesture simultaneously repels.

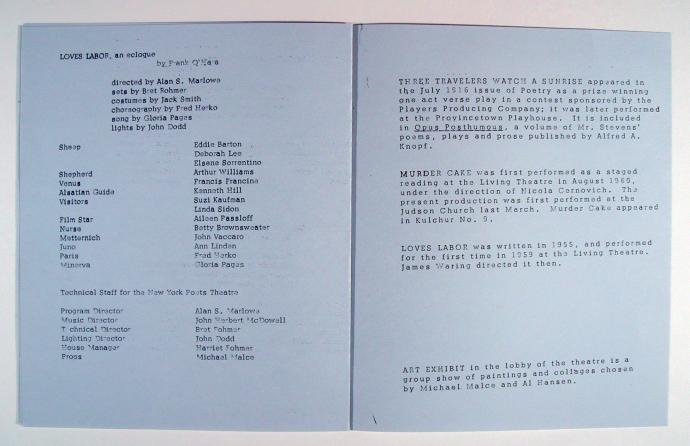

Program for "One-act plays by Diane DiPrima, Frank O'Hara and Wallace Stevens," performed from February 14 - March 27, 1964. Image courtesy the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin.

The short play was not only part of the Poets Theatre’s brief life, but also has more perennial implications as a meditation on the Poets Theatre itself. The poem-cum-play’s infidelities to the theatrical genre offer an allegory of cultural politics: the stereotypically private form of poetry enters the public theatre, discarding insularity in favor of intervention. Erudite in its references, the play nonetheless thumbs its nose at academic pieties that would pose the strict segregation of those genres in the first place. Perhaps as a result of this generic indeterminacy, the play barely exists now. In contrast to the easily available paperback editions of O’Hara’s poems, his selected plays were published only once by Johns Hopkins University Press in 1978 as Amorous Nightmares of Delay. This issue of access adds an extra ironic turn to the play’s central concern for variety. A keyword of cultural politics, variety references the hope that providing alternatives to the status quo constitutes a cultural intervention that effects a political intervention. Yet the play ultimately takes an ambivalent stance toward this proposition: while its manic energy would seem to advocate for variety, the play nonetheless finally critiques variety as precipitating disaster. At the end of the play the famous politician Metternich speaks prophetically:

The day has become a destruction,

all things meretricious are precious

for variety is let loose upon the world. (161)

A contemporary unease among critics and activists with the inherited traditions of cultural politics—the cri de coeur that the contemporary manifestations of capitalism have absorbed or foreclosed all alternatives—has much to do with the sense that variety itself has transformed into an index of totalizing commodification. At a time when this form of politics feels intolerable to many (as too naïve, ineffective, or even worse, complicit), a critical return to the moment when it was first forming as a response to postwar American society will go some way toward historicizing idealizations of the past and jaundiced eyes toward the present. The play’s campy sensibility—O’Hara calls it a “masque”—self-critically relates the play to the world of the Poets Theatre, to New York and its avant-garde and to even larger cultural shifts. In this light, the dynamic of the audience’s attraction and repulsion reads as an effect of the play’s own distantiation from and ambivalent feelings toward its cultural moment. The play speaks about its time as if it were already past. It is archly-nostalgic in that its celebration of a cultural moment slips into an elegiac mode. Yet O’Hara did not speak against variety per se, and his tombstone is inscribed with the words “Grace to be born and live as variously as possible.” The grammatical distance between “variety” and “variously” is an opportunity to make some sense of this seeming contradiction in attitude: variety, a noun, evokes the material or even the commodity, while variously, an adverb, is a modifier and potentially open-ended proliferator.

Inasmuch as the play concerns cultural politics, it also then limns the cultural field in which it would intervene. The play achieves its arch-nostalgic time warp by re-routing its contemporary concerns and characters through the classical form of the eclogue. In a further turn of the screw, the play raises the possibility that this naturalized scenario is not an invention of its own but is the cultivated self-image of the postwar U.S. Thus the play, although short, recedes into a “bad infinity” of spurious prehistories that form the obverse of postwar optimism for an “American century.” The play ends with ominous circularity: “Tomorrow I must seek / new pastures for my sheep” (161).1 Through its failure to constitute a plot and its refusal of development, the play succeeds in executing the seemingly impossible acrobatics of critiquing the culture it constitutes and participates in, elevating ambivalence into a politics.

A metaphor of light charts its durational progress and suggests gradual conceptual illumination. Ostensible but unrealistic stage directions at the beginning of each scene describe changing light over a landscape and ultimate revelation: “The mountain of lapis-lazuli is seen to be merely one eye of the goddess Minerva” (158). With this anticlimactic reversal of the trope of unveiling, the play rejects the conventional narrative of revelation. The unsettling suggestion that the landscape looks back, that the intention of the artist and gaze of the audience must face one another, reinforces the sense that the play’s impetus is not a movement toward resolution but is the determination to sustain an attitude of melancholic frustration. In the program for the New York Poets Theatre performance at the New Bowery Theatre, O’Hara writes “This masque is not ‘about’ something; depressingly, it is something.” In other words, the play does not exist separately from its object of concern. Instead it constitutes or adds to it. Further, O’Hara’s negative feelings toward it as some thing suggests that he has placed the act of creation itself under critique, that the play enters a world already too crowded with things.

With the different narratives evoked by its various characters, the play develops sophisticated political metaphors of the 1960s. The Shepherd and Metternich stand out as figures for different forms of government and their respective models of power. The shepherd, as Father and Law, metaphorizes an older form of pre-Christian pastoral power, while Metternich, the consummate European politician and master of the art of government, replaces the Shepherd in accordance with the emergence of the modern state.2 In this political context, the role of a third character, the senator, becomes more interesting, and his appearance becomes legible as an instance of a bureaucratic form of governmentality. “And now you observe life,” he says, evoking the Cold War fetishization of science and central planning.)

The historical shift implied in the contrast between the Shepherd and Metternich, as representatives of different models of power, recapitulates the entire sweep of the evolution of Western government, from sovereignty to bureaucracy, from the care for subjects to the science of populations. This abstract evocation of politics intersects with O’Hara’s concrete experiences in two significant ways. First, it speaks to his relation to bureaucracy. The contrast between the Shepherd and Metternich echoes the contrast between the institutional art world and the avant-garde. O’Hara, working in the Museum of Modern Art’s administration but also circulating through the downtown arts scene, ensconced himself in two different and potentially conflicting social positions. He would have been sensitive to the structure of bureaucracy and aware of its enabling and restrictive relation to artistic practice (in that bureaucracy provides a target of critique and a source of funding). Second, O’Hara expressed these models of power as dichotomous forms of personal relationships: personal interaction and intimacy (the Shepherd) versus critical distance and expertise (Metternich). The evocation of politics in turn raises the possibility of influence, including artistic influence, as a form of cultural politics that takes place through personal relationships. O’Hara’s participation in the art world involved both forms of power and forms of artistic influence, and in Loves Labor, these forms appear as working through degrees of personal interaction from the completely anonymous to the sexually intimate.

Working alongside the contrasting archetypes cast by the Shepherd and Metternich, Venus, Juno, Paris and Minerva complete the cast of the classical myth of the Judgment of Paris, effectively constituting a silent play-within-the-play. Denuded of its plot, the Judgment of Paris appears only in its cast of characters, yet it nonetheless lends the play its solid credentials of cultural capital. In the original myth, an aesthetic decision becomes a political decision, and the stakes of beauty and vanity become the stakes of war and death. The myth offers the inseparability of aesthetics and politics, traced back to the Greek origin of those received terms. Also it presents a conservative story about gender: a man judges a woman’s beauty, receives a woman as bride in return. In its new twentieth century context the Judgment of Paris appears as a beauty pageant appropriate to a society of spectacle. In a consumer society, it appears as a narrative of false choices and disparity of power. “But surely one thing is as good as another!” (160) Paris says in an attempt to exculpate himself by appealing to the false equivalencies of commodification. Even the goddesses are not immune to the publicity-machine and reification of their gender, and their sacrilegious self-abjection suggests an eschatological vision. When Minerva wonders, “I wonder if Cecil Beaton is here with his gun” (158), she indicates her constant awareness of the potential of the male gaze, even when it is not obviously there, and even when it is that of a gay fashion photographer.

The whirlwind of publicity and its signs in the play—actresses, cameras, neon—becomes a dilemma. The Shepherd, his duties disrupted, laments:

What a terrible day it’s been

for the flock! the dust!

the noise! its incredible.

And all this horrid publicity.

Will it ever be cool again? (159)

The rhetorical question stages a conflict between publicity and coolness (“cool” slangily denoting cultural caché) that comments on the desirability of marginality and obscurity in an underground art scene. Along these lines, we might return to the play’s title by inserting an apostrophe to yield “Love’s Labor.” In this version, the title evokes the idea of art as labor of love (rather than a civic labor or a utilitarian one). This idea repeats the old ideology of l’art pour l’art. Predictably, the play is ambivalent about such pieties: the sheep respond to the Shepherd’s lament “O shut up, you big dope.” This impatience, one which anticipates our own contemporary feelings, speaks to the difficulty for cultural politics to negotiate between several tendencies entailing from its fraught definition of the relation of art to dominant culture. The alienation of aesthetics from the social realm—a commonplace of twentieth century theory—allows art a certain autonomy at the same time as it denies it the possibility of direct intervention. From this perspective, one form of cultural politics asserts the play’s social relevance even within its underground position, or even especially from this position in regards to dominant culture. But this valuation in turn falls prey to an economy that structures ‘coolness’ as a form of cultural capital. The critical distance of alienation is lost and the play becomes another commodity: “This masque is not ‘about’ something; depressingly, it is something.”

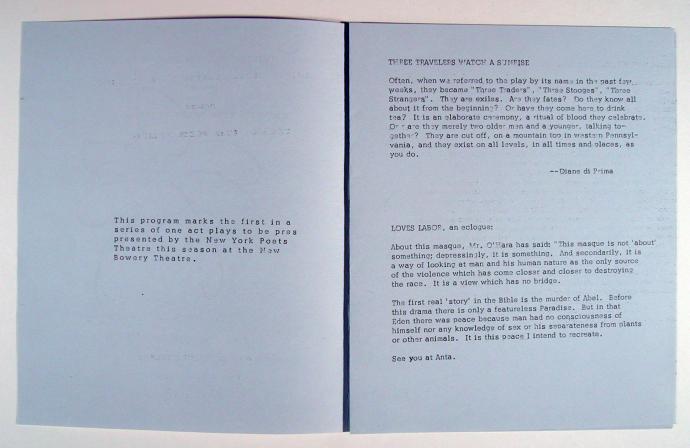

An untitled (c. 1958 - 1962) work by Jack Smith, the costume designer for the New York Poets Theatre production of Loves Labor.

Paris supplies one index of intervention into dominant taste—‘offense’— when he says “I wonder if I have offended anybody?” O’Hara poses him as the negative image against which to develop the idea of the artist as provocateur. But O’Hara is not so naive as to unequivocally celebrate the latter figure. In any case the play does not sustain the sincerity needed to shore up an anachronism of the enfant terrible. Nonetheless, a send-up of public opinion was one of the play’s accomplishments, a fact confirmed by the negative reaction to it. Diane di Prima reported in her autobiography, “Of course, many folks who had come along with us this far absolutely hated Loves Labor."3 Moreover, the staging follows the general momentum of the 1960s and its particular subcultures of camp, kitsch and drag that formed as reactions to the culture industry. Nonetheless, the play implicates these tendencies in its apocalyptic vision: “the day has become a destruction… variety is let loose upon the world.” Di Prima noted, “Frank had given us the entire Decline of the West in less than four typewritten pages of hilarious poetry.”4 How can the play itself not be somehow immanent to the terminus of that fall, if not its endpoint?

I have proposed to think about midcentury cultural politics, in particular the cutting camp of O’Hara’s “masque,” as a critical edge to wield against current forms of ennui, yet this is not to propose replacing it with nostalgia for that form of cultural politics itself. The play’s ambivalence about its own politics—its arch-nostalgia cuts both ways—could potentially be a resource for a more rigorous ambivalence about ours. Yet if the secret fear of cultural politics is that no one is listening, this accounts for something of the play’s painfulness: the characters know they are speaking past one another, that their brash proclamations isolate them. The reader feels this pain more acutely, now that the play speaks to a mostly empty audience.

This article is part of "There Is No Taste in Theatre: It is a Medium," edited by Chelsea Weathers. Other parts of this project include:

A Partial Index of the American Theatre for Poets, Inc., 1961–1965

Creating Context by Chelsea Weathers

An interview with Aileen Passloff by Robin Williams

Theatre Quote Unquote:* The Expansive Gestures of the New York Poets Theatre (American Theatre for Poets, Inc.) by Leanne Gilbertson

and our Editor's Statement

- 1. Page citations are to Amorous Nightmares of Delay: Selected Plays. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.)

- 2. I am indebted to Stefan Mattesich for this connection; see Michel Foucault. Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1977–1978. Trans. Graham Burchell. New York & Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. Foucault, when constructing his genealogy of governmentality as a technology of power, traces pastoral power from its ancient origins through the Christian pastorate to the secular state. He identifies the minister, rather than the king, as the new pastor that presides over the shift.

- 3. Diane di Prima, Recollections of My Life as a Woman: The New York Years. (New York: Viking, 2001.)

- 4. Ibid.